River crossing at Belgrade

The technical corps receive very little attention in the literature of the Great War. Most of the attention is paid to the trenches, which often show the horrors of war, and the infantry troops involved in it. Collectors’ favorite areas are assault troop relics or cap badges showing them. However, the technical corps have carried out much more interesting and exciting activities in several respects. One of these was the river-crossing.

To get the infantry and then the artillery through water barriers: this is how we can briefly describe this activity. But if we go into detail, we’ll find out immediately how multifaceted this activity can be! On smaller watercourses, simple pedestrian bridges can be built from locally found timber. On larger rivers, the first wave of crossing takes place in rowing boats. After the bridgehead has been invaded, a bridge can be built. Bridging wider streams is only possible with dedicated special devices and vehicles with pontoons and bridge elements mounted on them. In such cases, river crossings may also need to be continued by larger vessels and barks. Since these give a large target, the preparation of the crossing presupposes the elimination of enemy artillery. So artillery preparation is also required. In many times, the mine lock installed in the water must be disarmed. This activity can be carried out by mine-picking vessels. Finally, towards the end of the war, the bridge had to be secured against enemy air strikes. The list shows that a more serious stream-through required coordinated action of several weapons.

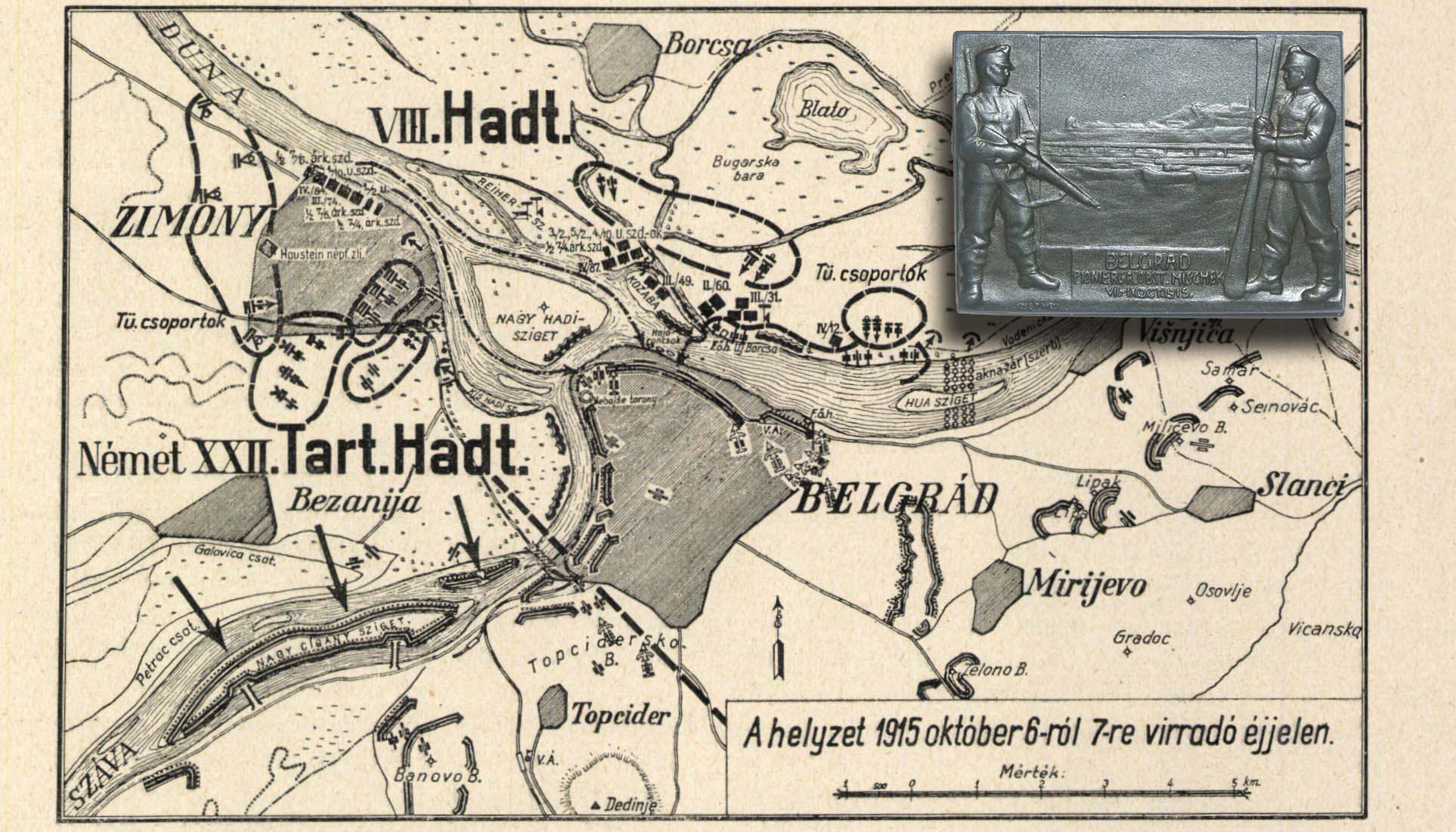

There is a very interesting cap badge which is relatively less appreciated due to its large number of copies. It captures the event of a larger scale river crossing. According to the inscription, this badge commemorates the operation of Colonel Mischek’s pioneer group from October 7-9, 1915. The date, and the Belgrade skyline in the background, shows exactly what’s going on. This is the date of the Monarchy’s second attack on Serbia. One of the main directions of the attack was Belgrade. Here, the crossing of the Danube and the Sava rivers was carried out by the group. The book on Hungarian technical corps details this action in a particularly long chapter. This was an outstandingly large crossing operation paralleled only by the Piave maneuver in 1918. Practically, an entire army, two corps, had to change coasts in combat conditions.

According to the description, the Mischek Pioneer Group was responsible for the transfer of the Austro-Hungarian VIII Corps. The corps included the 57th and 59th divisions (with mountain brigades 2, 6, 9 and 18, and an insurgent brigade as a corps reserve). The staff of these units could be approximately 30,000 men. The Danube had to be crossed, right across the city of Belgrade. But the background to the operation was provided by troops settled in a larger area. The elements of the war bridge were drawn up in Dunapentele and shipped first to Újvidék and then to Belgrade. The support artillery was stationed in Zimony and Pancsova. The bridge material needed to the crossing was transported to the site on October 6, the day before the action.

The crossing of the VIII Corps was preceded by artillery preparations of 20 heavy and 90 light batteries. This happened on the afternoon and evening of October 6. At 2:30 a.m., the enemy’s first lines were put under snare fire. The shipping of troops was then initiated at 3:00 a.m. In the first wave, three battalions of the two divisions crossed with pontoon boats and steam shuttles. The crossing took place in some places long after the artillery fire strike. They were attacked from the defensive lines that have been reorganized in the meantime. Defenders in these places have been able to inflict heavy losses on the crossing devices. Some of the boats in the darkness got lost. Despite the losses, the Monarchy’s troops managed to transfer an infantry force that could eliminate the resistance in the first lines. This opened the way for the second wave and ensured the conditions for the construction of the war bridge.

The Mischek Group was made up of the 1, 3 and 5th companies of the 2nd pioneer battalion, the 1st and 4th centuries of the 10th pioneer battalion, and the 7/4, 7/6 and 9/8 sapper companies. That’s a total of about 1,000 to 1,200 people. The technical material used was 12 war bridge columns (with 192 pontoons), 60 wooden boats 14 ships, 13 speedboats and 6 steam ferries (3100 seats, steam ferries were able to transfer 2 battalions or 2 artillery batteries in one go). The bridge, which was later built, was a pontoon bridge 350 meters long.

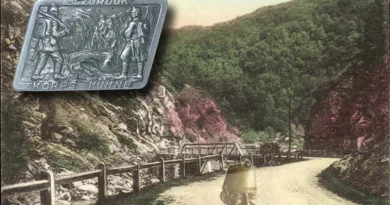

Colonel Johann Mischek was described in the book as an experienced technical officer of great professional authority. Even before the Belgrade crossing, he was entrusted with several major tasks, mainly similar river crossings. For example, the book mentions the July 1915 Vistula crossing, during which Austro-Hungarian pioneers helped German troops’ crossing. This action is depicted on the above post card, another nice piece from Gábor Csiszér’s collection. Presumably the Belgrade operation described here may have been the largest enterprise he ran. On the Kappenabzeichen of the action, a sapper is standing with a gun in his hand and a digger on his back from the left. A pioneer stands on the right with a paddle in his hand. The field post card presented in the post is marked with the unit stamp of the Mischek pioneer group. It was sent in March 1916. From all this, I conclude that the Vistula crossing group was together for at least a few months or a year. In October, other technical units were allocated to the group. But the formation’s command and some kind of cadre may have persisted, only different squadrons located in the changing action sites were assigned from time to time. I haven’t found any better answers to these organizational questions yet.