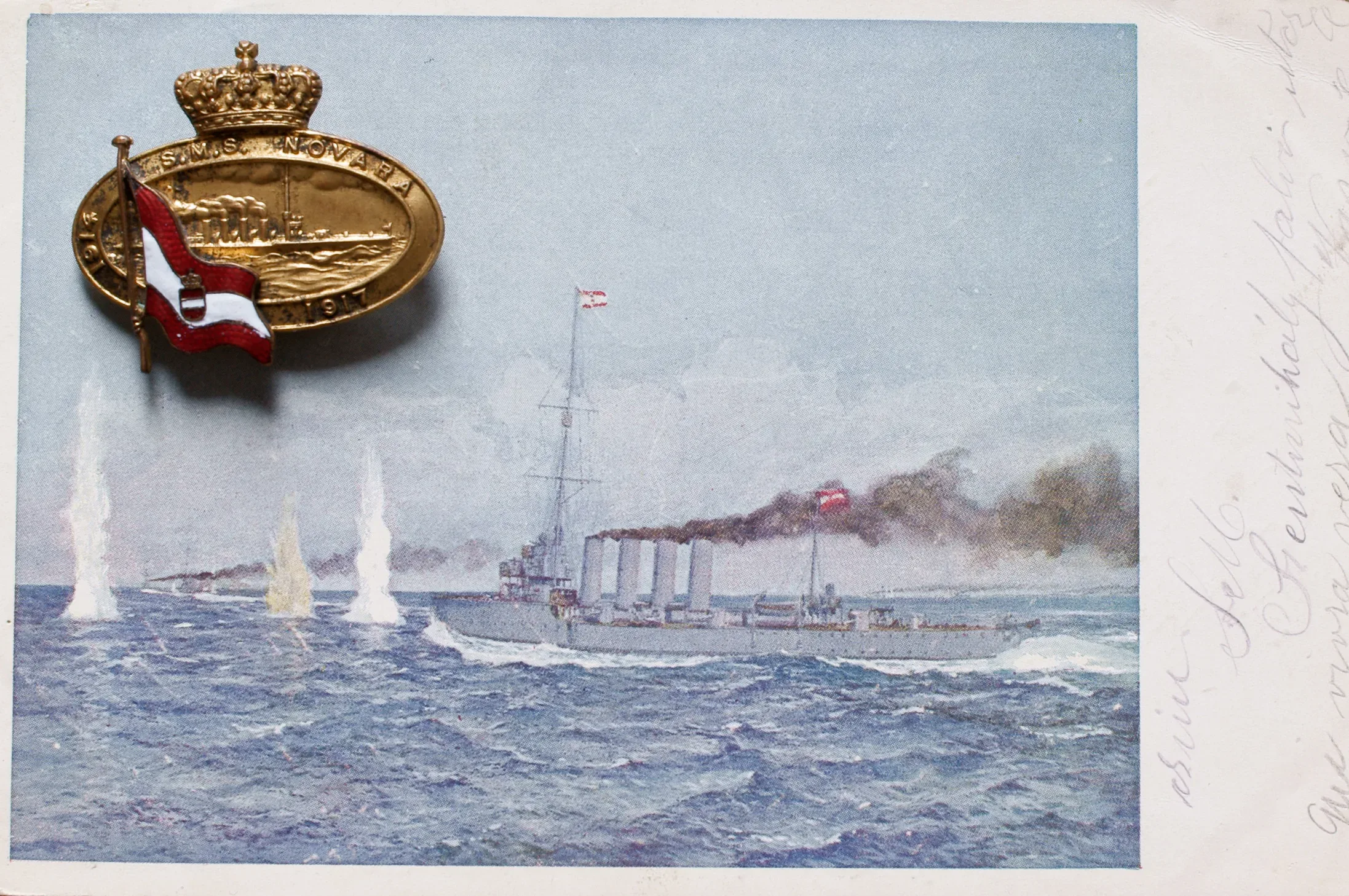

May, 1917: the Otranto battle

I wrote relatively little about the Austro-Hungarian navy. The main reason for this is that essentially only three more serious operations were carried out by the surface fleet. The first occurred at dawn on the first day of the Italian attack, when military installations and infrastructure on the far shore of the Adriatic were hit by artillery from ships. The second action took place two years later in May 1917.

The Monarchy did not want to risk the surface units in the face of multiple superior forces. Therefore, he used submarines to disrupt the trade traffic of the Entente in the Mediterranean. The enemy tried to prevent the Austro-Hungarian submarines from leaving the Adriatic with a sea lock. The sea lock of Otranto stretched from the heel of the Italian boot to the island of Corfu. This consisted of smaller gunboats and merchant ships patrolling towing steel nets. A fixed net lock was installed on smaller sections. It was difficult to get through the rudimentary diving boats under or next to the nets, several got stuck in the lock.

The Naval Command therefore decided to destroy the lock. The task was given to Miklós Horthy, who at the time was the captain of the fast cruiser Novara. The action took place on May 15, 1917. The attack group consisted of three fast, modern cruisers of the Helgoland class and two destroyers. At dawn on the 15th, the Austro-Hungarian alliance quickly sank fourteen of the 47 British steamers of the sea lock and damaged four, thereby breaking the sea lock. At the news of the attack, two British cruisers and five destroyers raced to the scene from the port of Brindisi. At 9:30 a.m., the British opened fire on the Austro-Hungarian ships. By developing artificial fog, they tried to escape the range of larger sized British guns. The Novara was hit and its captain was wounded. At 11:30 a.m., even wounded, Horthy took command back and requested help from the nearby Cattaro naval base. When reinforcements arrived, the British ships turned back to Brindisi.

The battle brought success to the Monarchy, as it sank 16 enemy ships without losing any of its own ships. The loss of life on the side of the Entente was 116 dead and 48 wounded, while on the own side there were 15 dead and 31 wounded. The psychological effect of the victory was even more important. And for Horthy’s career, it was of decisive importance.