Col di Lana 2.

Immediately after the declaration of war against the Monarchy, Italy set about taking advantage of the surprise to advance along the country’s borders. In practice, this meant that he took the initiative on all important front sections, regardless of the natural obstacles to the attack in these places. The struggles fought in the summer of 1915 achieved results of local significance at some points. Thus, for example, it was possible to capture the mountain Krn, which dominates the upper course of the Isonzo, but not the other nearby peaks, so a narrow wedge was created, which was inconvenient for the defense, but did not threaten the rapid collapse of the front section.

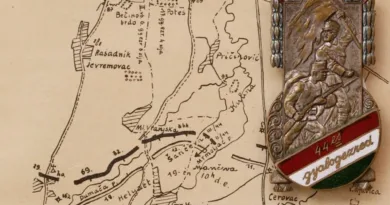

Gaining ground in the Dolomites in East Tyrol was just as difficult. In this section of the front as well, the Italian attack was only able to capture one peak. Such was the Col di Lana, the peak that the Italians only called “the mountain of blood”. There was already a post about the operations here (this), now I would like to present a recently found drawing that illustrates the mine warfare on the mountain. The plan was for the attacking Italian force to break through the mountain range that lined the former border and reach the river valleys behind the mountains. Following these, it would have been possible to reach the important transport and logistics hubs of Tyrol, Brixen in the east and Trento in the south. After breaking through the Dolomites, Brixen could have become accessible via the Puster Valley.

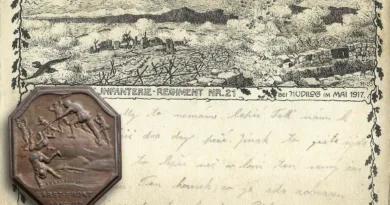

After the unsuccessful attempts in 1915, both sides started “mine work”. They tried to destroy the enemy positions located close to each other with underground explosions, and then advance by occupying the gap hit there. On April 17, 1916, after a 5-ton Italian mine was detonated, the position and crew of the Tyrolean Kaiserjager company defending on the top of the Col di Lana was destroyed. The Italians took the hilltop. In the contemporary photo attached to the post, you can see that there was a narrow saddle in the immediate vicinity of this peak. On the other side of this stands the almost equally high Mt Sief, which remained in Austrian hands. In 1916-17, the struggle continued on and below this narrow saddle.

In the accompanying drawing, we can see that the Italians exploded under the Austrian positions on two occasions in 1917, but were unable to reach Mt Sief. The situation changed when the leadership of the Austrian troops decided to stop combat opportunities here. On October 21, the engineer troops destroyed the saddle connecting the two peaks with a 45-ton explosion. The massive explosion changed the shape of the mountain range. The exploded part can also be seen in the panoramic photo. Today, the mountain climbing trips launched here are enterprises that require serious climbing performance. In the end, the Italian attack did not lead to any tangible military results. It inflicted an irreparable wound on the landscape and claimed the lives of many thousands of soldiers on both sides.

The Kappenabzeichen attached to the post is the badge of the artillery command of the region. In the background you can see the mountain range of the Dolomites with the Col-di-Lana. I chose this badge because the interpretation of the name Buchenstein caused me trouble for a long time. The map showing the region and some internet research revealed the meaning of this as well. You can see the inscription next to the serpentine road leading to the foot of the mountain group. More broadly, the valley area between the Marmolata block and the Ampezzo settlement was called Buchenstein. The Austro-Hungarian heavy artillery batteries were located on Marmolata together with the command post.

[…] siege of Col di Lana in the western part of the mountain range has already been discussed (here and here). At the eastern edge, the almost 3,000-meter peak of the Rotwand dominates the terrain. It closes […]