Defense of Kirlibaba

Kirlibaba and Dorna Vatra are wonderfully situated resorts in the Eastern Carpathians. Dorna Vatra began to develop as a spa resort during the Monarchy on the border of Bukovina and Transylvania, based on the local hot springs between the mountains. Kirlibaba remained more of a mining town. The area is crossed by the Aranyos Beszterce River, which flows out of the Beszterce mountains, and collects water from the small tributaries Kirlibaba and Cibó. Above the river valleys are mountains around 1500 meters, which were still largely covered by untouched primeval forest. In difficult mountain terrain, of course, it was not possible to build cohesive trenches to protect against the enemy. Rather, the dominant heights and mountain peaks were used as a point of defense to fend off enemy attacks. Such were the Jedul, Capul, and Tatarka mountain peaks around Kirlibaba, which were defended by the 40th Infantry Division against Russian attacks from the summer of 1916 until the fall of 1917.

As a result of the Brusilov offensive, much of Bukovina, which was recaptured in the summer of 1915, was lost again, so that in the summer of 1916 the line of defense of the Monarchy was again in the Carpathians. Initially the front ended here, but as Romania entered the war it streched along the eastern and southern borders of Transylvania. In support of the Romanian attack, the Russians also initiated serious actions in the autumn of 1916 against the most important strongholds of the defense, Capul and Jedul. After the Romanians were knocked out, the fighting subsided. The Russian Revolution of 1917 also made an impact, leaving the Russian fighting spirit at bay. Nevertheless, there was constant fighting in this front section, surprise attacks, reconnaissance actions. It was not large mass attacks that took place in the mountainous terrain, but the disturbing actions of smaller, section or squadron groups that took advantage of the terrain to try to get into the enemy’s back with surprise actions.

The documentation of the fighting around Kirlibaba is very rich. A memoir of all the regiments of the 40th Infantry Division (the “Fokos Division”) fighting here was published, detailing the activities of the regiments. You can know everything down to the smallest detail, and there is plenty of imagery available. Using all this, Hungarian front researchers found for example the war monument of the 6th Honvéd Infantry Regiment in the Kirlibaba Valley, which is now being renovated by the local authorities.

I have already presented some of my own materials in the post describing the badge of the 40th heavy howitzer battery. The first of the pictures attached here shows one of their guns with steeply elevated cannon barrel in the valley of the Kirlibaba stream. The steeply laid barrel clearly illustrates the mountain application of the weapon.

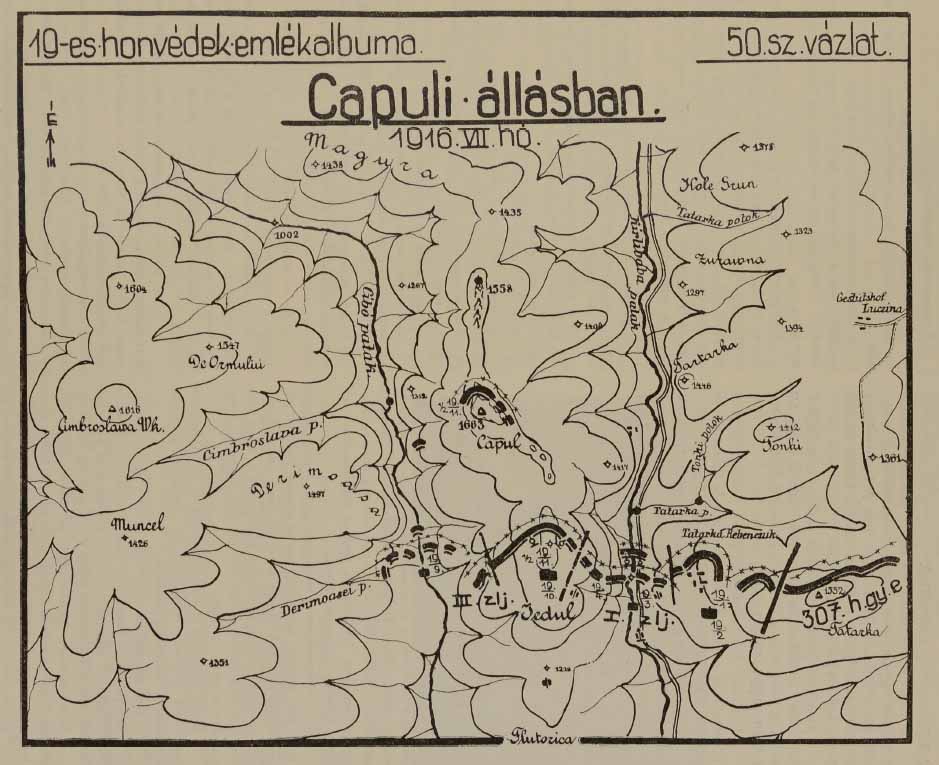

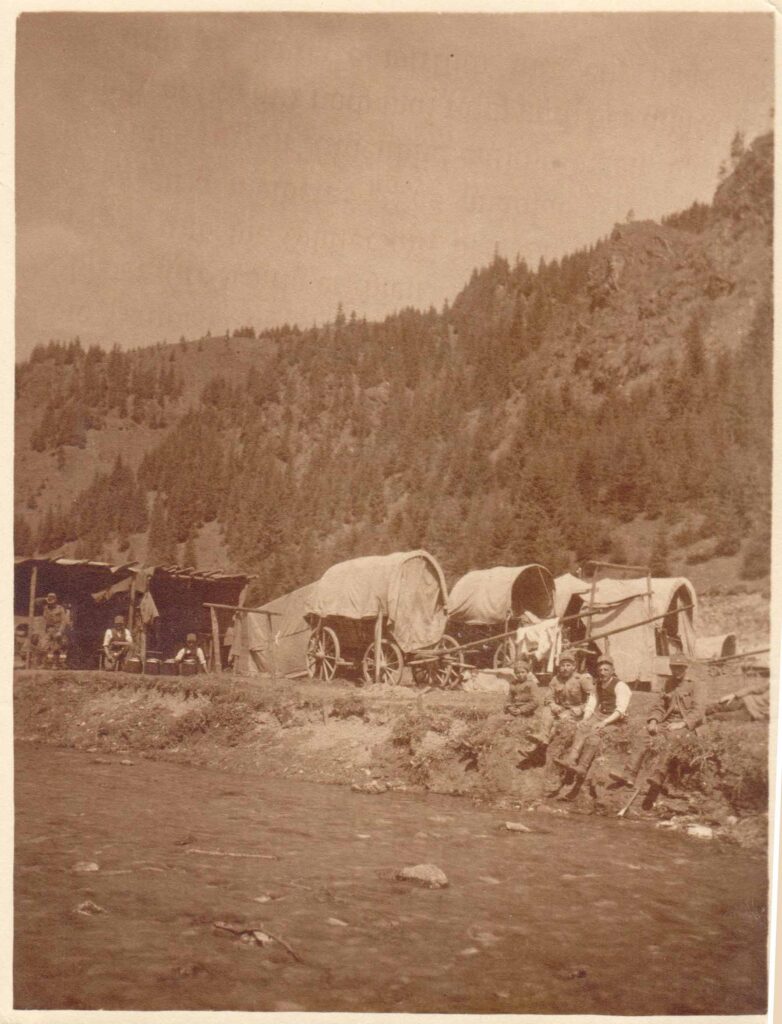

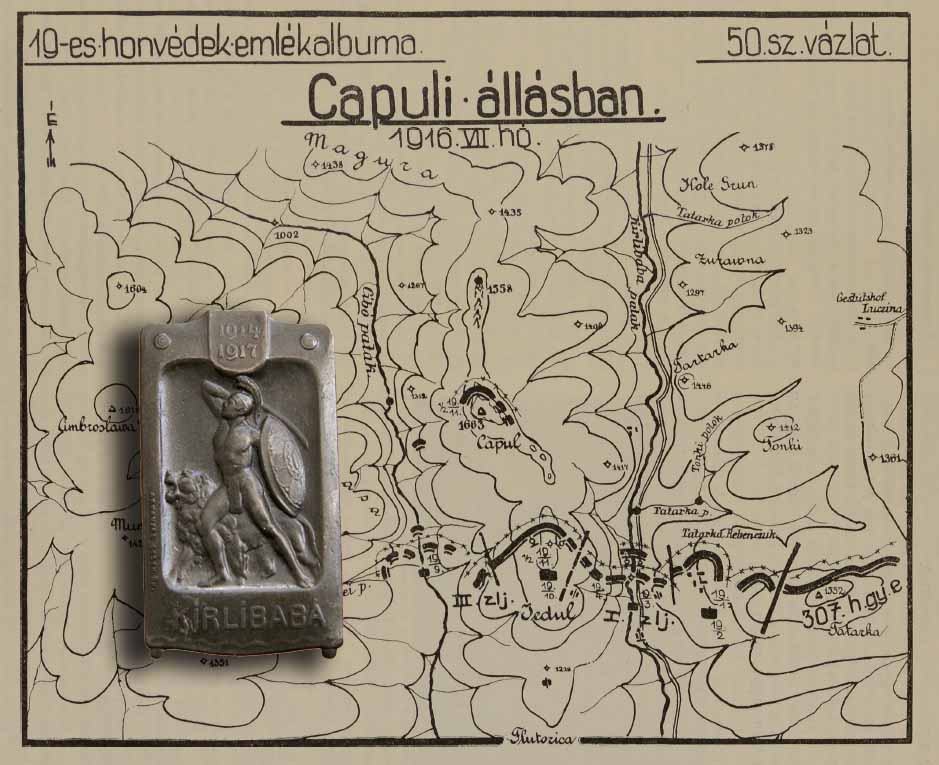

The attached map shows a sketch of the front section near Kirlibaba. To the left is the Cibó river, to the right the Kirlibaba stream flows south, and they are pouring into the Aranyos Beszterce, not shown on the map, just outside the settlement of Kirlibaba. The howitzer battery was thus installed in the valley of this stream. The second image shows the bottom of the creek valley, where the vehicles of the 40th heavy howitzer battery train were camping. Both pictures were taken in August 1916.

The third image is April 1917. At that time the main line of defense was settled around the Capul peak. In the fall of 1916, the 40th Division was able to consolidate the Capul line of defense, which was shown on the 1916 map as a forward position. The photo was taken from the top of the former main line of defense, Jedul, but unfortunately it does not look forward, towards Capul, but backwards, to the west. In any case, it shows the character of the countryside.

The Kirlibaba badge is one of the front badges of the Arkanzas company. The company produced the badges in a row about the main lines of defense of the Eastern Front like a kind of war diary. Some of them show trench positions, front sections. Another typical solution is to represent an allegorical figure. Here the main figure of the badge is a Greek warrior, based on his helmet and shield, a hoplite accompanied by a lion in the war.

[…] This division included the 6th, 19th, 29th and 30th honvéd infantry regiments, which received crews from the central areas of the Kingdom of Hungary, mainly from the Danube-Tisza area. They fought on the Russian front for most of the war. They took part in stopping the Russian invasion of Galicia in the winter of 1914-15 and then in the great offensive of the spring and summer of 1915. At the end of the year, they defended their positions in Bukovina against the troops of General Ivanov in the area of the municipalities of Toporoutz and Rarancze, north of Czernowicz, the capital of Bukovina, at a huge loss. In the fall of 1916, they were commanded to repel the Romanian invasion in Transylvania, and for more than a year at that time they fought in the foothills of the Carpathians around Dorna Vatra and Kirlibaba. […]

[…] (Battle Axe) Infantry Division. The reader could get a taste of the division’s struggles here and here. The fokos was systematized and applied in melee in all regiments of the division. His […]

[…] The 302nd Infantry Regiment was raised in early 1915, like the other regiments of the 51st division, and replaced one of the four regiments of the 23rd Division captured at Przemysl. The badge faithfully follows the regiment’s war events until 1917. The ancient chariot and the warrior holding a laurel branch on it are an allegory of victory in war. Not very often, but ancient depictions also occur on the badges, for example on the one prepared in memory of the Kirlibaba battle site mentioned on this badge, which I wrote about here. […]