Fighter aces on the Italian front

In military aviation, the most successful fighter pilots since the Great War have been called “aces”. It is customary to list here all air soldiers who have achieved at least five certified air victories in the fight against enemy aircraft. During the Great War, the series of air victories was also augmented by the destruction of enemy airships and tied observation balloons.

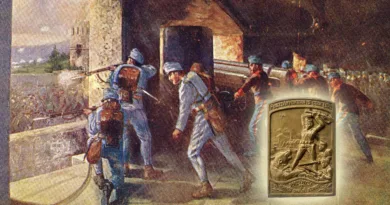

The use of airplanes gradually gained ground in the war. I’ve written about this before here. Air combat was extremely rare at first, and at that time there were still relatively few fighters designed specifically for air combat. Fighters’ battles against each other became commonplace in the last two years of the war, on the Western Front and on the Italian battlefield. On this front, the pilots of the Monarchy also won the most laurels and aerial victories. The superiority of the Entente had also become increasingly depressing in the number and quality of their aircraft. Therefore, even the best pilots and the biggest aces could easily get into a hopeless combat situation. The dominance was able to knock down the best, which usually ended in death. At that time, parachuting was in its infancy too, so if the pilot could not make a forced landing with the damaged plane he was usually killed in the wreckage.

The Monarchy’s most successful pilot was Godwin von Brumowski, who was certified for a total of 35 air victories, 12 of which were joint with other pilots. Brumowski served as an artillery officer on the Russian front at the 6th Artillery Brigade. He transferred from there and took up flight combat operations from July 1915. He first served in the 1st Squadron in Bukovina. Until July 1916 as an observer of two-seater aircraft, later as an aircraft pilot. He entered the Italian front in November 1916 and achieved his fifth air victory here in January 1917 in the 41st Fighter Squadron. He reaped the bulk of his aerial victories after that. In part, the aircraft designed for air combat was helpful. Equally important, of course, was that at this stage of the war, and especially on the Italian front, the activity of the enemy air force was orders of magnitude more intense than in the east. There were more targets, more enemy planes.

Brumowski’s plane was, of course, damaged several times. On February 1, 1918, due to the hits of enemy fighters, the fuel tank in the upper wing of his plane caught fire. With a tremendous coldblooded skill and luck, he managed to put his plane down and leave it intact before it burned out completely. Three days later, in an air combat with eight English fighters, the wing stiffener of his plane was damaged. During the forced landing, his plane flipped over and was completely shattered. His last sortie took place on June 19, when he achieved his last 35th air victory and then landed with 37 hits in his plane. At the highest instruction, he was no longer allowed to fly after that: pilot aces with high propaganda value were decimated.

Brumowski stands next to his death-headed plane to the right of the opening picture. Next to him is Frank Linke-Crawford, the Monarchy’s fourth most successful fighter pilot with 27 air victories. He died on July 30, 1918. He attacked Italian fighters with a group of four planes. During a sharp turn in the air, the wings of his plane detached and the plane crashed.

The most successful Hungarian pilot was József Kiss with 19 certified air victories. Several times Kiss did not simply shot enemy planes, but forced his opponent to land on the ground. Because of his success and chivalry, he was uniquely awarded the Gold Bravery Medal three times as NCO. Kiss flew in the 55th Fighter Squadron on the Italian Front in 1917-18. He also achieved most of his aerial victories then and here. On January 27, 1918, he took off to expel an Italian plane attacking the own airport (Pergine). Soon more Italian planes arrived on the scene and Kiss’s machine guns got stuck. He had to flee. After 10 minutes of turning, he was shot in the stomach. He fled to a nearby gorge valley, from where he returned to his airport. He recovered from his bad wound in May and he boarded the plane again. Eyewitnesses said he had not yet regained his old flying skill at this time. On May 24, during a long air battle, a Canadian pilot shot down his plane. Prior to his funeral ceremony on May 27, 1918, a large enemy group appeared over Pergine. A package was dropped. It had a wreath with the inscription on the ribbon in English, French and Italian: “Our last greeting to the brave comrade.”

The badges of the “air walking” units were very varied. The simpler stuck badge in the opening image in this post could certainly have been a bazaar item, anyone could buy it. The other badge, which is a semi-finished, unnumbered badge, is much more special, more expensive. It is very similar to the regular pilot skill badge. It is essentially a small version of it. The inscription on the bottom plate refers to the Italian front. The number of flying squadrons stationed there could be engraved on the bottom line. Because of the demanding workmanship and similarity to the pilot badge, I think that this badge could be worn only by the flight staff and not by ground service crew.

[…] more and more frequent. Earlier, I reported on the death of two Austro-Hungarian flying aces, József Kiss and Frank Linke-Crawford. In August 1918, the fight continued with the same intensity and there […]