Latest posts

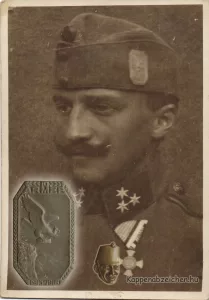

February 9, 2026He was the commander of the 22nd Landwehr regiment. I could only obtain the most primary information about him. Almost nothing about his wartime activities, despite the fact that he was a very well-decorated officer as a lieutenant colonel. He was born in the small town of Stanau (now Stankov, in the south of Bohemia, near the Austrian border), in 1869. He lived a long life, dying in 1953 in Klosterneuburg, Austria.

The photograph of him was taken on November 17, 1917. I found a description of an outstanding battlefield action. Emperor Charles bestowed upon him a noble title (von Grazigna) for this. For the successful defense of a height east of Gradiska, when he repelled the attack of two Italian regiments, personally leading the regiment’s command staff, and recaptured lost positions, while capturing 12 officers and 300 enemy soldiers. According to a document dated September 27, 1918, he received the title of knight from the emperor at that time.

The 22nd Landwehr Regiment was from Bukovina, and its headquarters were in Czernowitz in peacetime. The photo in the post is interesting because the small horn badge number 22 can be seen on the commander’s cap. It means then, that these badges were worn not only by the Feldjagers, but also by soldiers of the Landwehr regiments. I am attaching the plate badge of the 22nd regiment to the post, on which the name Grazigna is also listed among the names of battlefields. [...]

Read more...

January 15, 2026The badges of the cavalry regiments are particularly beautiful and expensive. Many of them are beautifully enameled. The shape of the badges was often similar. This is especially striking in the dragoon regiments. The standing oval shape with the imperial crown on top is very common.

That is why it is difficult to distinguish the cap badges seen in the group photos from each other. These full-body photos taken from a little further away could not capture the inscription of the cap badges, especially the motif on it. You can roughly guess what we are seeing based on the shape of the badge. However, since there are a number standing oval, crowned badges, it is difficult to choose.

The oval shapes are of course not completely identical. There are longer and fatter versions. This is an important and quite easily recognizable criterion. The next characteristic, also related to the shape of the badge, is whether there is any protruding plate on the oval (on which the regiment number or perhaps the year was usually engraved)? And of course, the decisive factor would be the badge inscription itself, the central field, but due to the enameling, it is almost always distorted by reflection.

In this Fortepan picture, I see the 6th Dragoon regiment badge as a possibility, but the 7th is also a strong candidate. The fact that the badge image seems to have a pattern of the L monogram seen on it speaks in favor of the 7th. At the same time, the crown of the 7th regiment’s badge is a little wider than what we see in the picture, and the shield below also seems to have a different shape. It is like that of the 6th Dragoons badge.

Sometimes the puzzle is blurred even further as some artillery regiments also had oval badges similar to this. The 6th Field Howitzer Regiment, for example, could be considered. But the oval there has a different shape, so it can be ruled out. [...]

Read more...

January 11, 2026Colonel Baron Trenck could enter the hall of famous personalities and generals because he was the hereditary owner of the 53rd Zagreb Infantry Regiment. Despite his military actions, though daring and successful, he still deserved the death penalty, which Maria Theresa changed from a pardon to life imprisonment.

He lived between 1711 and 1749. His estates were mainly in Slavonia, hence the choice to become the owner of the 53. regiment. Trenck was a self-willed, unbridled soldier. First, he participated in the wars against the Turks as a Russian mercenary, and then he joined the War of the Austrian Succession. To help Maria Theresa, he recruited a mixed Croatian and Serbian-speaking crew on his estates at his own expense. They became the “Trenk-panduren”. Although his unit belonged to the Austrian regular army, he often carried out actions arbitrarily, without the knowledge of the high command or against its orders. For example, he robbed the Prussian king’s camp in the Battle of Soor on September 30, 1745, almost taking the king prisoner. This action was the last straw for him, as he did not march into the battle itself despite orders. He was subsequently arrested and imprisoned, where he committed suicide in 1749.

Trenck and his pandurs enjoyed great popularity during his lifetime. After his death, he became a famous figure in Serbian and Croatian folklore. This popularity made him an hereditary regimental owner. Two beautiful letter seals were also made about him and his pandurs. The regimental badge is decorated with the coat of arms of Zagreb. [...]

Read more...

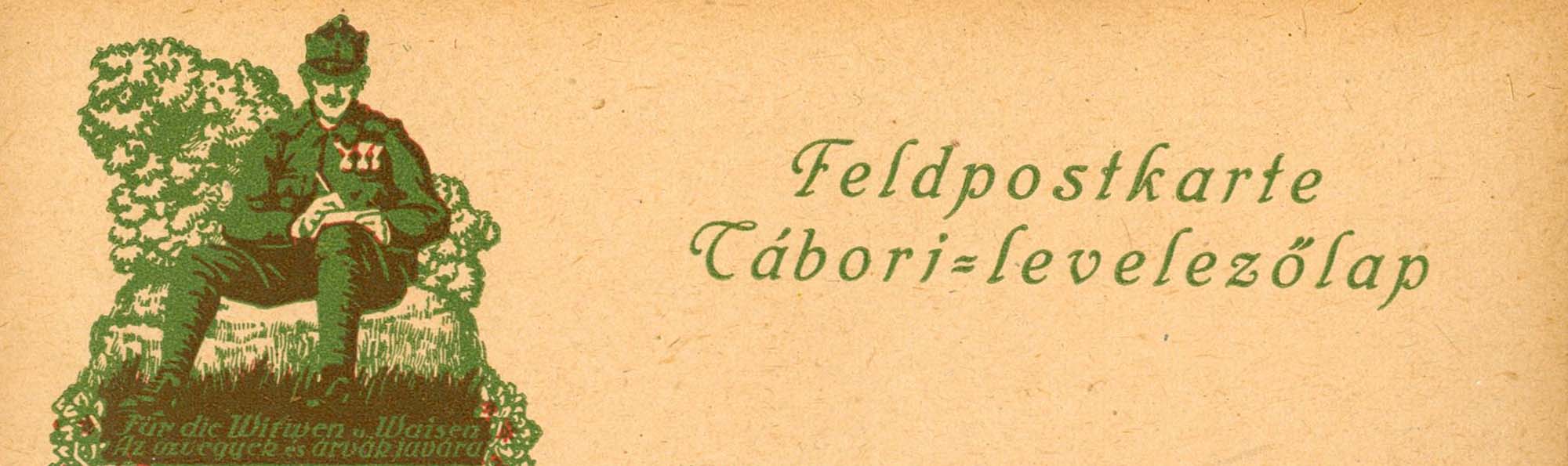

January 11, 2026The 71st Infantry Regiment and its plate badge have been discussed here before. At that time, the theme of the badge was the fortress in the background, which is on the outskirts of the city of Trencsén. Trencsén was the headquarters of the regiment, which operated mostly with Slovak personnel.

In this post, the plaque serving as the basis for the badge is the main feature, as well as the postcard made from it. The military of the Monarchy, especially the units associated with cities and regions, paid great attention to providing war relief. Obviously, the public office of a larger city was the most suitable for this. The civil organizations participating in the aid work, often the local governments of the settlements, were at the forefront of the initiative. Thus, in many places, not only war nailing serving war goals in general were organized (you can read about this here). In many places, motifs related to the regiment appeared in public spaces and on various objects made available for the general public. [...]

Read more...

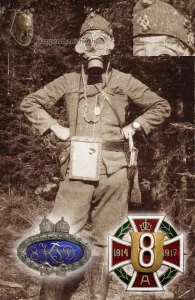

January 7, 2026Sometimes it is not easy to decipher the connection between the many badges worn on field caps. The officer in the latest image of Fortepan has three badges on his cap. In addition, he also has a “medal” hanging around his neck, which, if you look closely, is identical to the badge of the 30th Honvéd Infantry Regiment. This badge was also made with a pin, and a leather strap could be threaded into the opening at the top, and the medal could be hung on a belt or around the neck. That’s not what’s interesting. It’s not even the badge of the 40th Division on the front of the cap, because the 30th Regiment belonged to it.

The main feature is the two cavalry badges on the side of the cap. One is clearly recognizable as the Kappenabzeichen of the 8th Lancers Regiment. The other is from the 8th Cavalry Division. These two badges also belong together, the Lancers were assigned to this division.

But how do the boots end up on the table, the cavalry badge next to the infantry? Usually, the caps were pinned with badges that the soldiers were personally attached to, mainly through their position. It is a fact that in 1916-17, both divisions, the cavalry and the infantry, fought in the Carpathians as part of the XI. Corps. So they could have been close to each other. I can only assume that we are seeing an officer who was transferred from the 30. Honvéd Infantry Regiment to the cavalry division. The tassel on the bayonet indicates that he was Honvéd infantry officer. He could have performed some kind of liaison function, perhaps. [...]

Read more...

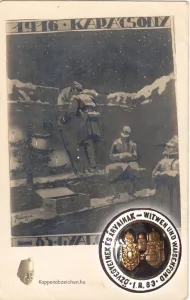

December 25, 2025I wish all readers of the site merry Christmas and lots of success, joy and good health for the upcoming new year!

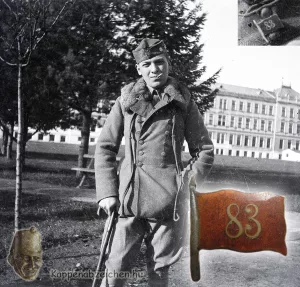

The card presented here was issued by the support fund of IR 83. The badge too. [...]

Read more...

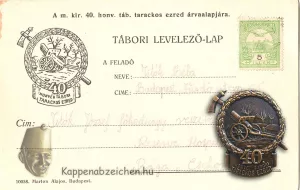

December 23, 2025This card has been hiding among my materials for a long time. The correspondence card is very often seen in the philatelic offer. Since it is constantly in sight, I forgot that it is indeed possible to write a post about this badge. All the more so, since the badge is a very detailed, beautiful work. Of course, it cannot be considered very rare either.

It is worth noting some general information about the regiment that the Hungarian honvéd artillery only began to be established in 1913, first with the cannon regiments. As a result, the Hungarian honvéd artillery did not have any howitzer units or heavy artillery until 1915. The army divisions received “borrowed” howitzer troops from the artillery of the “joint” forces. From these, or from the batteries of the honvéd cannon regiments, the first howitzer divisions were formed after retraining. The number of the guns increased and thus the units reached the size of a regiment, both in terms of equipment and the number of trained artillerymen. But this only happened in 1916. In the artillery regiments of the Hungarian honvéd, the organizational framework of the howitzer units began to be established in September 1915. In March 1916, the 40th Hungarian Army Howitzer Regiment was formed, assigned to the 40th Infantry Division. The artillery brigade of the 40th Division, including the howitzer regiment, operated under the subordination of this division until the end of the war. [...]

Read more...

December 17, 2025It was inspiring for the war effort if international cooperation was demonstrated. Everyone looked with appreciation at Germany’s military capabilities and technical equipment. Turkey was able to provide a wide geographical perspective for the alliance of the Central Powers. War propaganda also tried to emphasize international military cooperation.

Most of the propaganda badges of the Monarchy combined the national colors of the four allied countries. Often, soldiers from the four countries were shown, but in this regard, mainly the soldiers of the Monarchy and Germany were featured together. In some cases, we see joint portraits of the rulers on the badges. The best known and most common of these is the badge decorated with the busts of the four emperors. A postcard was also decorated with this Kappenabzeichen, which I have presented here. Now we can see a wearing photo with this badge. [...]

Read more...

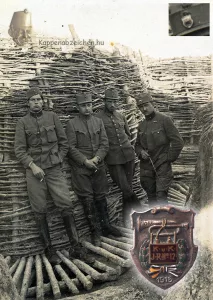

December 15, 2025Another interesting photo from Fortepan. Four officers face the camera in Galician trenches. The sides and bottom of the trench, the wickerwork and the slatted footpath are interesting The installations prevented the soil from moving due to the heavy rain and helped traffic at the bottom of the trench. Three badges can be seen on the caps of three officers. Of these, the 12th Infantry Regiment is the most recognizable, where the design of the badge image also appears.

A small triangular badge on the caps of the officer in the middle and left is the badge of the higher unit, the 33rd Division. The number is not visible on this image, but this badge is clearly visible on the cap of Colonel Magerl-Kouffheim, the former commander of the 12th introduced here. The third badge is seen more from the side, and judging by its shape, it may be the frequently seen badge of the Böhm-Ermolli Army Group. You can read more information about the 12’s history and battles here. [...]

Read more...

December 12, 2025As is known, the second line of national defense was called Landsturm in the Austrian provinces and Népfölkelés (Insurgents) in the Hungarian part of the Monarchy. The mostly older reservists sent here mainly performed construction, supply and control duties behind the fronts. These troops were organized into battalions set up on a territorial basis, following the division of the Landwehr and Honvéd military organization. In addition, in the first year of the war, each Landwehr and Honvéd district also set up a Landsturm (or Népfölkelő) infantry regiment. These were not intended for frontline activity either, nevertheless most of them were deployed in the Galician battles already in August 1914. There, they largely crumbled by the end of the year, and most of them were disbanded. Relatively few Hungarian Népfölkelő regiments remained, slightly more Austrian Landsturm. These were later filled with soldiers of younger ages, so they became fully combat-ready.

The badge of the 13th Landsturm Regiment still depicts the classic elderly, well-to-do daddy with a pipe in his hand. Don’t let the idyllic image fool you, the 13th Landsturm Regiment from the Sudetenland took part in many battles. The regiment was originally part of the Krakow garrison and the staff of the city fortress. In 1915, it was transferred to the 121st Brigade, then to the 92nd Brigade in 1916. They fought in the Hofmann Corps on the Eastern Front, then came under German command. From 1917 until the end of the war, they were a regiment of the 46th Rifle Division. They also ended the war on the Italian front. The wearing photo was apparently taken on the Eastern Front. On the left side of the picture we see Germans in helmets, on the right side are the 13ers. [...]

Read more...

Recent comments

Szanyi Miklós on Transylvanian RangersCould be.

Emiliano Donati on Transylvanian RangersThis kind of hook is good? Is known on other

Szanyi Miklós on Transylvanian RangersSeems good, the hook is different. If the material is

THE HIGHLIGHTS

Your daily dose of inspiration

February 9, 2026He was the commander of the 22nd Landwehr regiment. I could only obtain the most primary information about him. Almost nothing about his wartime activities, despite the fact that he was a very well-decorated officer as a lieutenant colonel. He was born in the small town of Stanau (now Stankov, in the south of Bohemia, near the Austrian border), in 1869. He lived a long life, dying in 1953 in Klosterneuburg, Austria.

The photograph of him was taken on November 17, 1917. I found a description of an outstanding battlefield action. Emperor Charles bestowed upon him a noble title (von Grazigna) for this. For the successful defense of a height east of Gradiska, when he repelled the attack of two Italian regiments, personally leading the regiment’s command staff, and recaptured lost positions, while capturing 12 officers and 300 enemy soldiers. According to a document dated September 27, 1918, he received the title of knight from the emperor at that time.

The 22nd Landwehr Regiment was from Bukovina, and its headquarters were in Czernowitz in peacetime. The photo in the post is interesting because the small horn badge number 22 can be seen on the commander’s cap. It means then, that these badges were worn not only by the Feldjagers, but also by soldiers of the Landwehr regiments. I am attaching the plate badge of the 22nd regiment to the post, on which the name Grazigna is also listed among the names of battlefields. [...]

Read more...

January 15, 2026The badges of the cavalry regiments are particularly beautiful and expensive. Many of them are beautifully enameled. The shape of the badges was often similar. This is especially striking in the dragoon regiments. The standing oval shape with the imperial crown on top is very common.

That is why it is difficult to distinguish the cap badges seen in the group photos from each other. These full-body photos taken from a little further away could not capture the inscription of the cap badges, especially the motif on it. You can roughly guess what we are seeing based on the shape of the badge. However, since there are a number standing oval, crowned badges, it is difficult to choose.

The oval shapes are of course not completely identical. There are longer and fatter versions. This is an important and quite easily recognizable criterion. The next characteristic, also related to the shape of the badge, is whether there is any protruding plate on the oval (on which the regiment number or perhaps the year was usually engraved)? And of course, the decisive factor would be the badge inscription itself, the central field, but due to the enameling, it is almost always distorted by reflection.

In this Fortepan picture, I see the 6th Dragoon regiment badge as a possibility, but the 7th is also a strong candidate. The fact that the badge image seems to have a pattern of the L monogram seen on it speaks in favor of the 7th. At the same time, the crown of the 7th regiment’s badge is a little wider than what we see in the picture, and the shield below also seems to have a different shape. It is like that of the 6th Dragoons badge.

Sometimes the puzzle is blurred even further as some artillery regiments also had oval badges similar to this. The 6th Field Howitzer Regiment, for example, could be considered. But the oval there has a different shape, so it can be ruled out. [...]

Read more...

January 11, 2026Colonel Baron Trenck could enter the hall of famous personalities and generals because he was the hereditary owner of the 53rd Zagreb Infantry Regiment. Despite his military actions, though daring and successful, he still deserved the death penalty, which Maria Theresa changed from a pardon to life imprisonment.

He lived between 1711 and 1749. His estates were mainly in Slavonia, hence the choice to become the owner of the 53. regiment. Trenck was a self-willed, unbridled soldier. First, he participated in the wars against the Turks as a Russian mercenary, and then he joined the War of the Austrian Succession. To help Maria Theresa, he recruited a mixed Croatian and Serbian-speaking crew on his estates at his own expense. They became the “Trenk-panduren”. Although his unit belonged to the Austrian regular army, he often carried out actions arbitrarily, without the knowledge of the high command or against its orders. For example, he robbed the Prussian king’s camp in the Battle of Soor on September 30, 1745, almost taking the king prisoner. This action was the last straw for him, as he did not march into the battle itself despite orders. He was subsequently arrested and imprisoned, where he committed suicide in 1749.

Trenck and his pandurs enjoyed great popularity during his lifetime. After his death, he became a famous figure in Serbian and Croatian folklore. This popularity made him an hereditary regimental owner. Two beautiful letter seals were also made about him and his pandurs. The regimental badge is decorated with the coat of arms of Zagreb. [...]

Read more...

January 11, 2026The 71st Infantry Regiment and its plate badge have been discussed here before. At that time, the theme of the badge was the fortress in the background, which is on the outskirts of the city of Trencsén. Trencsén was the headquarters of the regiment, which operated mostly with Slovak personnel.

In this post, the plaque serving as the basis for the badge is the main feature, as well as the postcard made from it. The military of the Monarchy, especially the units associated with cities and regions, paid great attention to providing war relief. Obviously, the public office of a larger city was the most suitable for this. The civil organizations participating in the aid work, often the local governments of the settlements, were at the forefront of the initiative. Thus, in many places, not only war nailing serving war goals in general were organized (you can read about this here). In many places, motifs related to the regiment appeared in public spaces and on various objects made available for the general public. [...]

Read more...

January 7, 2026Sometimes it is not easy to decipher the connection between the many badges worn on field caps. The officer in the latest image of Fortepan has three badges on his cap. In addition, he also has a “medal” hanging around his neck, which, if you look closely, is identical to the badge of the 30th Honvéd Infantry Regiment. This badge was also made with a pin, and a leather strap could be threaded into the opening at the top, and the medal could be hung on a belt or around the neck. That’s not what’s interesting. It’s not even the badge of the 40th Division on the front of the cap, because the 30th Regiment belonged to it.

The main feature is the two cavalry badges on the side of the cap. One is clearly recognizable as the Kappenabzeichen of the 8th Lancers Regiment. The other is from the 8th Cavalry Division. These two badges also belong together, the Lancers were assigned to this division.

But how do the boots end up on the table, the cavalry badge next to the infantry? Usually, the caps were pinned with badges that the soldiers were personally attached to, mainly through their position. It is a fact that in 1916-17, both divisions, the cavalry and the infantry, fought in the Carpathians as part of the XI. Corps. So they could have been close to each other. I can only assume that we are seeing an officer who was transferred from the 30. Honvéd Infantry Regiment to the cavalry division. The tassel on the bayonet indicates that he was Honvéd infantry officer. He could have performed some kind of liaison function, perhaps. [...]

Read more...

December 25, 2025I wish all readers of the site merry Christmas and lots of success, joy and good health for the upcoming new year!

The card presented here was issued by the support fund of IR 83. The badge too. [...]

Read more...

December 23, 2025This card has been hiding among my materials for a long time. The correspondence card is very often seen in the philatelic offer. Since it is constantly in sight, I forgot that it is indeed possible to write a post about this badge. All the more so, since the badge is a very detailed, beautiful work. Of course, it cannot be considered very rare either.

It is worth noting some general information about the regiment that the Hungarian honvéd artillery only began to be established in 1913, first with the cannon regiments. As a result, the Hungarian honvéd artillery did not have any howitzer units or heavy artillery until 1915. The army divisions received “borrowed” howitzer troops from the artillery of the “joint” forces. From these, or from the batteries of the honvéd cannon regiments, the first howitzer divisions were formed after retraining. The number of the guns increased and thus the units reached the size of a regiment, both in terms of equipment and the number of trained artillerymen. But this only happened in 1916. In the artillery regiments of the Hungarian honvéd, the organizational framework of the howitzer units began to be established in September 1915. In March 1916, the 40th Hungarian Army Howitzer Regiment was formed, assigned to the 40th Infantry Division. The artillery brigade of the 40th Division, including the howitzer regiment, operated under the subordination of this division until the end of the war. [...]

Read more...

December 17, 2025It was inspiring for the war effort if international cooperation was demonstrated. Everyone looked with appreciation at Germany’s military capabilities and technical equipment. Turkey was able to provide a wide geographical perspective for the alliance of the Central Powers. War propaganda also tried to emphasize international military cooperation.

Most of the propaganda badges of the Monarchy combined the national colors of the four allied countries. Often, soldiers from the four countries were shown, but in this regard, mainly the soldiers of the Monarchy and Germany were featured together. In some cases, we see joint portraits of the rulers on the badges. The best known and most common of these is the badge decorated with the busts of the four emperors. A postcard was also decorated with this Kappenabzeichen, which I have presented here. Now we can see a wearing photo with this badge. [...]

Read more...

December 15, 2025Another interesting photo from Fortepan. Four officers face the camera in Galician trenches. The sides and bottom of the trench, the wickerwork and the slatted footpath are interesting The installations prevented the soil from moving due to the heavy rain and helped traffic at the bottom of the trench. Three badges can be seen on the caps of three officers. Of these, the 12th Infantry Regiment is the most recognizable, where the design of the badge image also appears.

A small triangular badge on the caps of the officer in the middle and left is the badge of the higher unit, the 33rd Division. The number is not visible on this image, but this badge is clearly visible on the cap of Colonel Magerl-Kouffheim, the former commander of the 12th introduced here. The third badge is seen more from the side, and judging by its shape, it may be the frequently seen badge of the Böhm-Ermolli Army Group. You can read more information about the 12’s history and battles here. [...]

Read more...

December 12, 2025As is known, the second line of national defense was called Landsturm in the Austrian provinces and Népfölkelés (Insurgents) in the Hungarian part of the Monarchy. The mostly older reservists sent here mainly performed construction, supply and control duties behind the fronts. These troops were organized into battalions set up on a territorial basis, following the division of the Landwehr and Honvéd military organization. In addition, in the first year of the war, each Landwehr and Honvéd district also set up a Landsturm (or Népfölkelő) infantry regiment. These were not intended for frontline activity either, nevertheless most of them were deployed in the Galician battles already in August 1914. There, they largely crumbled by the end of the year, and most of them were disbanded. Relatively few Hungarian Népfölkelő regiments remained, slightly more Austrian Landsturm. These were later filled with soldiers of younger ages, so they became fully combat-ready.

The badge of the 13th Landsturm Regiment still depicts the classic elderly, well-to-do daddy with a pipe in his hand. Don’t let the idyllic image fool you, the 13th Landsturm Regiment from the Sudetenland took part in many battles. The regiment was originally part of the Krakow garrison and the staff of the city fortress. In 1915, it was transferred to the 121st Brigade, then to the 92nd Brigade in 1916. They fought in the Hofmann Corps on the Eastern Front, then came under German command. From 1917 until the end of the war, they were a regiment of the 46th Rifle Division. They also ended the war on the Italian front. The wearing photo was apparently taken on the Eastern Front. On the left side of the picture we see Germans in helmets, on the right side are the 13ers. [...]

Read more...

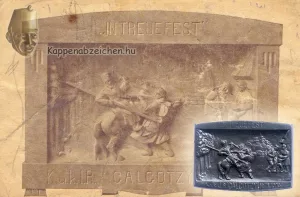

December 12, 2025In several posts I have referred to badges as “non-existent”. These are the rarest pieces that I have not or hardly ever encountered yet. The protagonist of this post is a badge that does not really exist, a badge design presumably. Obviously, we are not talking about the very common badge, the one depicting the regimental owner Archduke Friedrich, but the depiction seen on the postcard.

There are a few postcards on which you can see a badge design. Or at least we think so. Because the lack of actual occurrence of the object could also mean that only very few pieces were made, and they have all disappeared or are hidden away in the depths of collections, forgotten. But every year one or two never-before-seen pieces turn up. Maybe this promising-looking 1917 cap badge will appear one day. Until then, we will have to make do with the plate badge published here and the otherwise very decorative, bayonet version that I presented here. [...]

Read more...

December 10, 2025Army badges are among the first pieces for collectors of Great War badges. They were produced in huge numbers, and mostly in a variety of sizes and materials. The 4th Army badge, for example, was produced in three sizes and there were also copies made of steel, grey metal, tombac and silver.

The badge was produced with the years 1914-15, which is the most common. But a year later, it was also produced with the years 1914-16, which is rarer. I have uploaded this version to this post. Postcards embossed with the image of the badge were also made. The copy shown here was decorated with a beautiful spring bouquet drawn by a soldier who had the time [...]

Read more...

December 9, 2025An incredible wearing photo of a barely existing badge has been found on Fortepan! The plate badge of the 71st Infantry Regiment depicting the Trencsén castle and the numbered flag badge are well-known pieces. However, the badge depicting a charging infantryman is very rare. A wearing photo of it is even rarer. Specifically, I know only this Fortepan find.

The 71st Regiment belonged to the 14th Division, which included the regiments of the western part of the Highlands. Its headquarters was in Trenčín. Its personnel consisted predominantly of Slovak-speaking soldiers. In the initial stages of the Great War, they fought in Galicia and then in Bukovina, mainly in the IV. Corps. In the autumn of 1916, the division was transferred to the Italian front, first to the XVI. Corps (1917) on the Isonzo, then to the VII. and later to the XXIII. Corps (1918), on the lower reaches of the Piave. The battlefields and the year on the badge also refer to the fighting that took place on the Eastern Front. [...]

Read more...

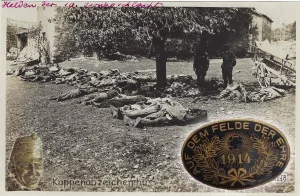

December 5, 2025More than one and a half million of the population of the Monarchy fell victim to the Great War. This huge number (about 3% of the total population, 10% of the adult male population fit for service) includes those who died in combat on the battlefield, the seriously wounded and the sick who died in hospitals. Of course, they were all heroes who died while fulfilling their oath to their homeland and the monarch. It is another question how heroic their death was, how exemplary their battlefield activity was. It is obvious that the majority did not seek glory, danger (and death). But the majority fulfilled their duty and the orders they received and died in the process.

From all this, the conclusion for me is that the gray, silent dead of the Great War deserve the same respect as those who died on the occasion of some special, noteworthy event. Thus, the badge in the post, which pays tribute to those who fell on the battlefield, pays tribute to all victims. According to the text in the background image, we see the dead corpses of 10th Battle of the Isonzo. They most likely rested first in a common grave and later in an ossuary in the huge war memorials built by the Italian government after the war. [...]

Read more...

December 4, 2025In the rapidly changing front situation during the years of the Great War, it happened several times that higher units, mostly brigades, or less often divisions, were organized from various troops at hand on the front line. Such was the recently presented Békési Brigade and such was the Papp Brigade.

I have written about Colonel Dániel Papp of the Engineering Corps here before. He began organizing his troop of volunteers in Bukovina at the turn of 1914/15. This group rose to brigade level in 1917. At that time, the 5th Insurgent Infantry Regiment, the Russ Group and several other insurgent supply battalions were part of its staff. I have also written about its history here. The unit’s badge appears in a new wearing photo found on Fortepan. The interesting thing about the picture is that on one of the field caps we can also see the badge of the Russ battalion. The opening page shows the silver version of the badge. The war metal design is in the middle of the text. [...]

Read more...

December 3, 2025Lieutenant Colonel Békési’s Insurgent Brigade was formed in March 1915 from the remnants of units that had already suffered heavy losses. Its largest unit was the 20th Insurgent Infantry Regiment, which in 1914 fought in the 101st Infantry Brigade in the 1st Army organization in Galicia. After its disbandment, it transferred to the newly organized Békési Brigade. This unit operated until April 1916. At that time, its number of fighters shrank again to one infantry regiment, so from then on it was only known as the Békési regiment, or the 20th Insurgent Infantry Regiment. The regiment survived until the end of the war, first in the 215th Infantry Brigade, then in the 130th Brigade. At the end of the war, it was ordered from Ukraine to Orsova, but it was no longer deployed there.

The special feature of the badge is that in addition to the regiment, it also commemorates the former infantry brigade. This is obviously connected through the person of the commander, Lieutenant Colonel Békési. It can be assumed that he ordered the badge for his troops. Yet, we do not see his portrait on the badge, but an infantry soldier. [...]

Read more...

December 2, 2025This regiment was formed from battalions of Western Hungary during the 1918 reorganization. Two were transferred here from the 83rd Infantry Regiment. The regiment’s commander was Colonel Antal Lehár, the brother of the composer Ferenc Lehár. A photo is well-known, showing the regiment commander holding his field cap with the badge of the 106th Regiment on. I have already presented this badge here.

Now it has reappeared again, because in the Fortepan treasure chest I came across an extremely good photograph on which two soldiers are wearing the badge. It depicts a camp scene, a large card battle, watched by dozens of fans. It could have been made in the summer or early autumn of 1918, since the badge clearly refers to the failed summer Piave offensive. The regiment performed well in this, managing to cross the Piave River, but due to the call off of the offensive, they had to return to their starting positions. Another interesting thing about the picture is that in addition to the badge, the regiment number can also be seen on one of the caps. [...]

Read more...

December 1, 2025It was a Styrian regiment, its crew came from the mixed Austrian-Slovenian part of the province. Its headquarters was in Görz, its battalions in Marburg (Maribor). The regiment was deployed as part of the 28th Division first in Galicia at Zloczów, Grodek and in the winter in the defense of the Beskids, then in 1915 at the Dniester. In 1916 they fought on the Italian front in the Austro-Hungarian offensive in Tyrol, then in August 1916 in the southern part of the Karst, at Hudi Log and on Mount Hermada. After the breakthrough at the end of 1917 they were deployed in the area of Monte Asolone, where they were stationed until the end of the war.

The regiment’s cap badge shows a mountain fortress in the background of a warrior with the helmet. This fort may even be the Fort Costesin on the Siebengemeinde Plateau, which was captured by the regiment during the 1916 offensive. [...]

Read more...

November 30, 2025Fortepan is a real treasure trove for researchers of old photographs. It even satisfies such exotic needs as wearing photos of Great War cap badges. What’s more, it publishes the best quality images without a doubt. This applies to the quality of the original images: there is selection. But also applies to the resolution of the available images: we get large image files.

So it is not surprising that one of the best images in which the regiment number can be clearly seen on the flag badge evoking the register number of the infantry regiments comes from this collection. I presented the flag badge of the 83rd Regiment on an equally rare field postcard here earlier. [...]

Read more...

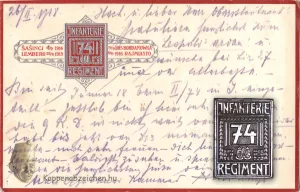

November 29, 2025The 74th was one of the Sudetenland infantry regiments. Its headquarters and one battalion were stationed in Jicin, and two more battalions in Reichenberg. It had a mixed Czech and German-speaking crew. It was assigned to the 29th Infantry Division, which was part of the XIV Corps at the beginning of the war, but this assignment changed frequently later. During the Great War, they were deployed on the Eastern Front until 1918. This is also evident in the battlefields listed on the field postcard used for the entry. Another interesting feature of the card is the color used, which is red, the same as the regiment’s lapel color. [...]

Read more...

November 28, 2025At the end of the Great War, after the collapse, hundreds of thousands of Hungarian soldiers returned home. After the lost war, Hungary’s neighbors, including former “comrades”, also set off on their conquest of Hungary, stimulated and equipped by the Entente. Unfortunately, the incompetent Hungarian government, which trusted the Entente promises of armistice, was busy with disarmament and did not deploy an adequate force to stop the invaders. The main force of the Hungarian resistance was the Székely Division. This unit successfully slowed the Romanian advance, but the multiple superiority of forces pushed them back from the borders of Transylvania to the edge of the Hungarian Great Plain in the early spring of 1919. After the communist takeover, there was an effort to develop the Hungarian military. This process was hindered by the fact that the political and military leadership of the Commune violently forced the ideological transformation of the military. Many volunteers were unwilling to do this, so the number of experienced, battle-tested crews hardly increased, but rather decreased. The recruitment was mainly carried out with ideologically motivated, but inexperienced urban citizens, workers, which meant a deterioration in quality compared to previous conditions.

The soldiers of the resistance teams of late 1918 and early 1919 who had served on the fronts were happy to wear their World War I Kappenabzeichen. In many cases, these badges were even retained in the Commune’s forces. Although the rank insignia and cap cocades were removed or replaced with a red star, the insignia reminiscent of wartime merits remained. In the photo attached to the entry, the soldiers of the Commune are wearing the badge of the assault troops of the 51st Honvéd Division. I have previously presented this insignia here. [...]

Read more...

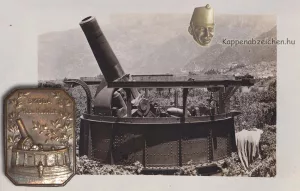

November 19, 2025Both the Monarchy and the German Empire produced giant 42 cm caliber guns. Their destructive power was enormous. However, their dead weight was also considerable, so they were not mobile devices. Preparing the firing position also required a day’s work of dozens of people. It could only be transported on dust-free roads, disassembled into 4 or 6 parts, on special tractors.

So the Monarchy changed the original plans and used it as a fixed built-in gun from 1915, primarily on the Italian front. The badge in the post depicts the giant gun in a gun turret that could be moved 360 degrees. The attached picture also shows such a battery position on the Italian front. More details about the gun can be read in a previous post here. [...]

Read more...

October 30, 2025At the outbreak of the Great War, there were six border patrol companies in the Austro-Hungarian army. Unlike the field rifle units, these were only company-sized, not battalion-sized, and were on duty in the Balkans (from 1915 in Macedonia and Albania). In the second half of 1916, they were expanded to battalion-sized. The 3rd, 5th and partly 6th companies had Hungarian crews. At the outbreak of the war, they were all fighting on the southern front as part of the 6th Army. In 1918, they were in Albania with the 47th Division.

I have not yet been able to gather more information about this special unit. Little trace of their activities remained, since they were only a few, small units. The recently discovered photo of a lieutenant is particularly rare. At the same time, it is also very interesting, since the badge of the Tyrolean Imperial Hunters can be seen on the cap of the border patrol lieutenant, as well as the cap ornament of the partridge feather worn by the Tyrolean riflemen. In my interpretation, this indicates that some of the border patrol battalions were deployed on the Italian front in the second half of the war. I have only found scattered information about the wartime history of the units, which did not include their use on the Italian front. I do not believe that there was an organizational connection between the border guards and the Tyrolean regiments.

Unfortunately, I cannot provide a photo of the rare collar badge, because I do not have such a badge. But the badge also appears on the badge of the 1st Border Guard Battalion. This has the same interesting feature as the photo: the soldier depicted on it is wearing the field cap of the Tyrolean riflemen with partridge feather decoration. In his hand, he is holding a long stick, which is also characteristic of Tyrolean units. According to these features, although the sources do not mention it, there should have been border guards transferred to Tyrol, the 1st battalion in any case. [...]

Read more...

October 27, 2025The Monarchy’s forces were organized into 9 armies. They were numbered 1-7, then 10th and 11th. I don’t know why there weren’t 8th and 9th armies. There must have been a reason for this, I’ll have to look into it. Each army had its own Kappenabzeichen. This insignia was generally created in the first two years of the war and lasted throughout, not much was changed. The 5th Army was an exception, which was renamed the Isonzo Army after the opening of the Italian front, which was followed by the creation of a new cap badge.

The badge of the 10th Army, however, did not change. From the beginning of the war, this army’s task was to secure the Italian border. After the Italian attack, the 5th Army was first reassigned, and then the 11th Army was created to defend Tyrol. At that time, the defense zone of the 10th Army naturally became narrower. The badge faithfully reflects the Italian front in any case. The crowned double-headed eagle soars above the mountainous landscape entrusted to its protection. [...]

Read more...

October 21, 2025In terms of personnel, nurses and nursing assistants were certainly the ones who took the most part in caring for wounded and sick soldiers. Because of the war, the capacity of healthcare institutions had to be increased enormously. This also necessitated an increase in the number of healthcare personnel needed to operate the institutions. While the training and appointment of doctors could not be done with the required speed, the training and employment of nursing personnel could be done much sooner and more flexibly.

Among the personnel, nurses also deserve special attention. Obviously, even 100 years ago, there were specialized nursing tasks that required serious professional preparation. For example, surgical assistance to surgeons treating the wounded required expertise. For this task, medical soldiers who were trained for this task within the framework of the army were mostly employed. Voluntary nurses were mainly involved in the care of convalescent patients. Given that full recovery from illness or injury took several weeks, during this time a very large number of auxiliary personnel took care of the ill soldiers: typically volunteer nurses.

The medical staff also wore badges, mostly with a red cross motif of various sizes and shapes. The nurse in the post is wearing the badges most often seen in the wearing photos. The round badge is visible on the front of the headscarf, the large oval on the neck of the blouse. Wearing it in the middle of the neck can be considered common. While working, the nurses wore a simple white scarf or bonnet to cover their hair, to the light material of which they could not attach the badges.

The decoration of the large oval badges with the Hungarian holy crown applique is very unique. Strangely, the Rudolf-crown decoration typical of the Austrian provinces cannot be seen. Is it possible that these badges were only worn in Hungary? [...]

Read more...

October 20, 2025He was born in Lugos in 1863. He prepared for a civilian career, but in 1884 he enrolled in the one-year volunteer course at the Ludovika Academy in Budapest. In 1888 he took the professional officer exam. He began his military career with the rank of lieutenant in Kassa. In that year he first completed the professional higher officer course in Budapest, then between 1889-91 the Vienna Military School. Immediately afterwards he was assigned to the General Staff. From 1911 he became the commander of the 10th Honvéd Infantry Regiment in Miskolc as a lieutenant colonel.

In the Great War he first led the 107th Insurgent Infantry Brigade, and then as a major general from May 1915 he was the commander of the legendary 16th Honvéd Mountain Brigade in the Karst Plateu (Doberdó), Mt dei Sei Busi area. He was given the title of Doberdó in memory of the battles here in his noble title, which he received in 1916. Due to health problems, he was placed on the reserve staff in 1916. At the end of the year, however, he was appointed commander of the 39th Honvéd Infantry Division, which was fighting on the borders of Transylvania. In this position, he achieved his greatest military success with his division on March 8-9, 1917, the capture of the Magyaros roof, an action that became famous for the outstandingly effective deployment of assault troops. For this feat, he received the highest royal recognition. He was a lieutenant general from August 1917. In 1918, he was appointed commander of the VII. Corps.

After the Great War, he primarily worked as a military history writer. He is the author of the 22-volume work “The Military History of the Hungarian Nation”, which is the largest professional work on this topic published to date. He changed his name to Bánlaky in 1931. He died in Üllő in October 1945.

This time I can attach a commemorative plaque to the post, not a badge. According to the inscription, Lieutenant General Breit had it made for the first anniversary of the occupation of Magyaros in March 1918. The date is evident from the workmanship, as the plaque is made of grey metal that was bronzed. [...]

Read more...

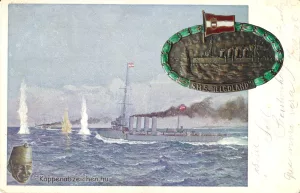

October 20, 2025I have already dealt with the breaching of the Ontranto Sea Lock in one of my posts (here). In addition to a brief description of the events, the focus was on one of the three modern fast cruisers participating in the attack, the lead ship, the Novara. Now the other main character of the action, the Helgoland is our topic, and that is through another beautiful badge depicting the ship.

The crews of both ships were decorated after the action, and badges were made commemorating the battle and the ships. Based on contemporary pictures, these were already worn by the sailors when the crews were decorated. The Helgoland badge is relatively rare, but you can’t see much of the Novara either. [...]

Read more...

October 3, 2025At last I had the opportunity to present one of the most beautiful cap badges featuring a nice wearing photo. The badge of the Archduke Peter Ferdinand Group with the lion and the coats of arms of the provinces entrusted to its defense below is a very well-made composition. So much so that the motif of the general assault team badge planned in 1918, the lion, was also taken from here. The coats of arms on the badge represent the provinces of Vorarlberg, Carinthia and Tyrol, where this higher unit fought as part of the 10th Army.

Not only is the presentation of the badge exciting me, but also the fact that I have now looked a little into the units assigned to the group. This group was established by the Vienna command at the beginning of 1917 and existed until August 1918, when it was merged into the V. Corps. The group was therefore not corps-sized, nevertheless, several divisions and infantry brigades were part of it. In 1917 these were the 59th Mountain Brigade and the 93rd Division. After the reorganization of the infantry in early 1918, the 163rd and 164th Infantry Brigades, the 22nd Schützen Division and the 1st Division were assigned here. In July 1918, the 1st Division was detached and became part of the Monarchy’s contingent fighting in France. In August 1918, the group was disbanded, and its troops were mostly taken over by the V Corps. [...]

Read more...

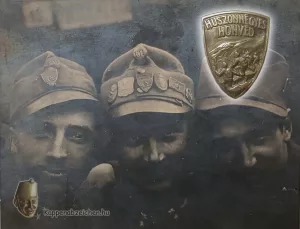

September 29, 2025The Székely Honvéd Regiment, the 24th, has already been featured with a nice wearing photo. Now I managed to upload another one. The badge on this one is also worn in the middle of the cap by the Honvéds.

I can’t tell much additional about the regiment based on the photo. I uploaded it again for the sake of the new picture [...]

Read more...

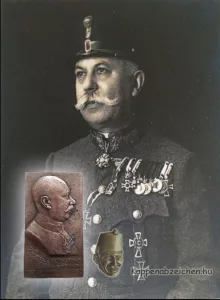

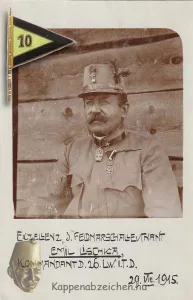

September 20, 2025A Czech military officer in the Austro-Hungarian army. He was born in 1859 in the town of Ceska Lipa. His active service lasted until May 1917, when he was retired. He retired to his hometown, where he died in 1929.

After completing basic military schools, he graduated as a lieutenant in 1878 and was appointed a company officer in the 43rd Infantry Regiment. From 1888 he served in Zadar, then in the military office of the 3rd Corps Command in Graz. In 1899 he became the chief of staff of the 15th Infantry Division with the rank of major. He was soon transferred to the Imperial Landwehr, where he taught at the Landwehr Officer School in Vienna. In 1906, he became the commander of the 36th Landwehr Infantry Regiment as a colonel. He was promoted to major general in 1911, and was then appointed commander of the 26th Infantry Division in Brno.

During the Great War, he commanded this division until July 1916, and then the 10th Division until May 1917, when he retired. The sources do not mention the reason for his retirement. There was no break in his promotion, and he was a lieutenant general when he retired. However, he was not appointed a corps commander. His decorations were also commensurate with his rank. As early as 1915, he received the 2nd class of the Order of the Iron Crown and the 2nd class of the Military Cross of Merit. At that time. It is true that he did not receive any further recognition after 1916.

Next to the portrait photo of the general, I can present the flag badge of the 10th Division, which he last commanded. Unfortunately, the 26th Landwehr Division did not have a cap badge. In the photo, he is wearing the Order of the Iron Crown, but not the Military Cross of Merit. It was probably awarded later, at the end of 1915. [...]

Read more...