Latest posts

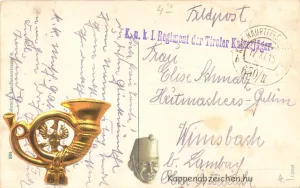

July 12, 2025The Tyrolean Kaiserjager were units corresponding to the regular regiments of the Kuk in this province with a special legal status. In principle, they could only be deployed to defend Tyrol, but in 1914 a legal loophole was found that allowed the Kaiserjager to be sent to Galicia. After the opening of the Italian front, however, they basically fought on this front section, in accordance with the original regulations.

Like the Feldjager battalions, the Imperial Guards had a horn on their hats and a small horn on their field caps. I will present the latter in this post. I can add a matching letter seal to it. [...]

Read more...

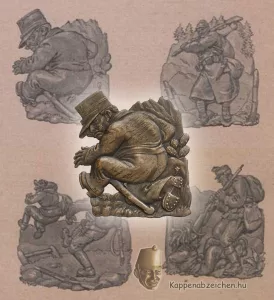

July 7, 2025The internet offers incredible opportunities even for old-fashioned guys like me who don’t really know how to use search engines optimally. I sometimes stumble upon exciting information based on the udder between the horns. The truth is that it’s not really possible to specifically search for something that we don’t know about.

There are quite a few mock badges that depict enemy soldiers in funny situations while the Monarchy’s bucks teach them the lesson. One such badge shows a fleeing Italian officer who, judging by his mustache, could be the Italian commander-in-chief, Cadorna. It’s a solid, nicely silver-plated badge. In terms of shape, material, and style, it’s similar to three other mock badges that I’ve shown here before. These badges are clearly the work of the same maker. Another series of mock badges in different look, material, and style was produced by the Arkanzas company, but these badges are typically “Arkanzas” and are otherwise also marked.

Until now, I knew nothing about the origin of the four badges that are different from the others, similar to each other, since they are not marked. Now, however, the internet has provided the solution. In one of the archives, I saw the badges on a page of a 1916 issue of the contemporary Hungarian satiric magazine, Borsszem Jankó. The intact text clearly identified the publisher as the designer (manufacturer). Even more interesting is that in addition to the four known types, there are also pictures of 5 other badges on the page. However, I have never had these as concrete, finished badges in my hands. They all depict enemies next to allied soldiers, in funny, uncomfortable poses. I do not know whether these were finally realized, or were they just drafts? [...]

Read more...

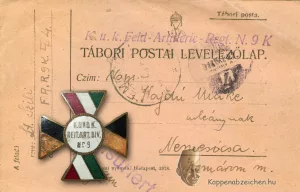

July 5, 2025The defense of the mountains south of the Pusster Valley was provided by the 49th Division. Its personnel varied a lot, but it was mainly composed of Tyrolean and Carinthian personnel. One of its most permanent units was the 96th Brigade. It consisted of several units, essentially mixed battalions, mostly Landsturm units from the area. I have already written about one episode of the defensive battle they fought here. In addition to the divisional badge, I have attached the badge of the 171st Landsturm to this entry.

The further mention of the division allows us to introduce another unit and another badge. This is the 165th Landsturm Battalion, which fought in the 96th Infantry Brigade in the Great War. I can attach a nicely stamped field correspondence card of the unit to the attached excellent badge. [...]

Read more...

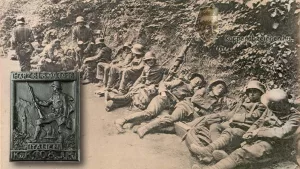

July 3, 2025The Monarchy’s army was significantly reorganized at the beginning of 1918. Instead of the previous infantry regiments with four battalions, regiments consisting of three battalions were created. Previously, one battalion received mountain training and was assigned to the mountain brigades. Now these have ceased to exist. New regiments were organized from the previously separated battalions. With the replacements, in many cases, the surplus units from the regiments with more than the required four battalions were also directed to the new regiments. In this way, more than 30 new regiments were formed this year.

The 108th Infantry Regiment eventually received four battalions, because in addition to the two 8th and one 99th battalions originally intended for this unit, the previously separated I/81st Battalion was also added. The upper edge of the badge presented in the post shows the numbers of the three regiments next to the founding date of March 1918.

The new regiments were deployed on the Italian front, so their badges bear the images and names of that front. I have previously shown the badge of the 106th Infantry Regiment here, which has the inscription Piave and the image of the Venetian lion. The badge of the 108th depicts a mountainous landscape with the inscription Italien (Italy). The 108th Regiment was assigned to the 60th Division, which was stationed in the mountainous terrain between the Siebengemeinden Plateau and the Piave, on both sides of the Brenta river. During the June 1918 offensive, the division was part of the unit attacking Mt Grappa. The attack failed to break through the Italian third line. Having achieved minimal territorial gains, it essentially stalled on the first day. The division’s regiments were largely destroyed by artillery fire from the mountains.

With this in mind, the question arises as to when the badge was made? I think it was just before the offensive, perhaps with the purpose of improving the morale. The location of the photo attached to the post is unknown. The use of assault helmets suggests a date of 1918, as does the summer clothing. It depicts tired soldiers resting in mountainous terrain. It could have been made on Grappa. [...]

Read more...

June 30, 2025Badges were also made with the coats of arms of the Austrian provinces and the coats of arms of many cities. These are mostly beautiful enamel pieces and are publications of the war relief offices.

The Styrian badge is a particularly beautiful, large badge. It depicts the provincial coat of arms. Apparently, anyone could buy it, like all war relief products. It is relatively rare to see such a thing on soldiers’ caps, badges depicting the ruler were more widely used. Some units’ own badges, such as the 44th or 26th Infantry Regiments are worn by many. In these regiments’ group photos, half of the soldiers are wearing the regimental badge. [...]

Read more...

June 26, 2025The most successful unit of the Monarchy’s navy was the submarine fleet. The larger surface units were not deployed at all, with the exception of cruisers and destroyers. Submarines, however, were constantly deployed. They achieved important successes, especially in disrupting enemy merchant shipping. They also successfully attacked some larger surface units of the Entente navy, but these cases were more likely to be accidental, not targeted attacks.

I have already shown the submariners’ service badge in a wearing photo here. Now I am attaching a picture of a sailor who has this badge on his jacket again. The subject of this post, however, is a submarine propaganda badge.

The service badge is always present in the few wearing photos I know of, I have not yet seen the submarine Kappenabzeichen made in a wide variety in military photos. From this I assume that these served more propaganda purposes. There are some plate badges depicting battle scenes, like the one we are presenting now. And there were the beautiful, colorful fire enamel badges, with dozens of different decorations. I think not only the latter, but also the plate badges belong more to the patriotic badge category. [...]

Read more...

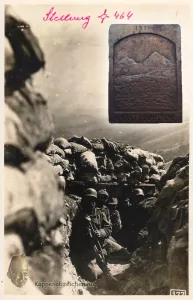

June 18, 2025The Italian front, which opened in 1915, had several front sections, each with a different character. In Tyrol, the fronts were mostly located between the peaks of high mountains, or in narrow passes between the peaks, which were mostly protected by fortresses. Further east, the mountains of Carinthia showed similar terrain. The Isonzo was the largest river near the border, with narrow valleys in its upper section, while the lower section had much larger and more extensive valleys. The estuary area was no longer mountainous, but rather hilly, more suitable for agricultural cultivation. Here, on the eastern bank of the river, lies the Karst plateau, the famous Doberdó battlefield.

The Karst is a hilly region, rising 100-120 meters above the river, and beyond the edge is flatter, with a highland character. Since there are no deep ravines or high peaks, it was easier for troops to move in this area. Moreover, one of the important Italian military objectives, Trieste and the Italian-populated areas of Istria, could be attacked in this direction. Therefore, the main direction of attack for most of the Italian campaigns was this area. Between May 1915 and August 1916, the front line stretched along the edge of the plateau. In the 6th Battle of the Isonzo, the Italians managed to push the front back by 20 km, to the central part of the plateau, to the front line of Fajti Hrib, Kostanjevica, Hermada.

The picture attached to the post depicts a detail of a trench on Fajti Hrib in 1917, vividly showing the improvised, shallow positions formed with great difficulty on the rocky plateau. The enemy could see into these from the heights in the background, so daytime movement in them was very dangerous. The attached badge is less detailed, we do not see trenches on it, only a landscape similar in nature to the photo. In the difficult conditions, both sides suffered huge losses [...]

Read more...

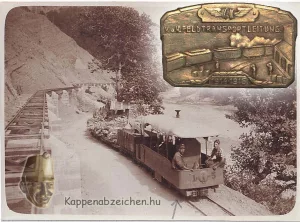

June 16, 2025The movement of troops and the provision of material supplies on all fronts of the Great War were basically carried out by railway. The expansion of capacity was continuous, and the reconstruction of tracks and equipment damaged by the enemy as the front moved was also a major task. Efforts were made to establish rail connections to places where there had been none before. The Prislop railway in the Eastern Carpathians was one such new railway line. Such was the case in several places with the railway line leading to the mountainous terrain of the Italian front, for example, the Julian Alps.

The lines close to the front were mostly narrow gauge. In several places they operated with electricity generated by small electric power plants. Such was the case, for example, with the line leading to Lake Bohinj. This reached the settlement of Ukanc. From there, a cable car system carried supplies to the high mountainous terrain of the Krn front.

The attached photo shows the wagons of a field railway. The badge chosen for the post, with its toy train-like train layout, fits in with these. [...]

Read more...

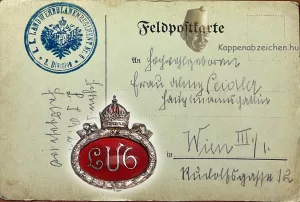

June 13, 2025The headquarters of the 6th Landwehr Uhlan Regiment was in the city of Wels, and it was founded here in 1885. The crew was mostly from the surroundings and from the Prague area. Therefore, soldiers with mixed Czech and German mother tongues served in the regiment. On the site of the regiment’s traditionalists, they emphasize the role of the 6th Uhlan in Limanowa battle, 1914. At that time, they provided the cavalry of the XIV Corps led by Lieutenant General Roth and successfully attacked the flank of the advancing Russian troops, threatening them with encirclement in the Neu-Sandez area. General Roth was later awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa for his achievements in the battle.

The regiment’s badge is a beautifully crafted fire enamel piece often seen in cavalry regiments. The oval disc contains the regiment’s letter and number, decorated with the Austrian imperial crown above. [...]

Read more...

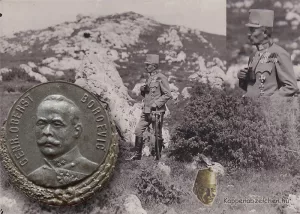

June 12, 2025Boroevic Svetozar was one of the most respected Austro-Hungarian generals. His successes during the Great War are evidenced by his advancement in rank and position. I have already described his career in detail here. He rose from the command of a division to the command of a front, in the most difficult defensive positions. In the winter of 1914-15, he was a corps commander in the Carpathians, then on the Italian front he became the commander of the 5th (Isonzo) Army, and then the entire Italian front. The photo attached to the entry was taken of the colonel general during this period.

During the war, perhaps because of his Croatian origin, he was not really popular in the general staff. His excellent leadership performance did not elevate him to the narrowest circle. His performance was honored with the Knight’s Cross of the Military Maria Theresa Order, but he did not become a confidant of the monarch or the chief of staff. The services of the outstanding military leader of the Monarchy were not claimed by the Yugoslav successor state either. He died in Austria in 1920. [...]

Read more...

Recent comments

Landsturm 165 - Sapkajelvény történetek on Rauchkofel – Pussterthal[…] units from the area. I have already written about

IR 108 Mt Grappa - Sapkajelvény történetek on Venice[…] images and names of that front. I have previously

Submarines (3) - Sapkajelvény történetek on Submarine crew member[…] have already shown the submariners’ service badge in a

THE HIGHLIGHTS

Your daily dose of inspiration

July 12, 2025The Tyrolean Kaiserjager were units corresponding to the regular regiments of the Kuk in this province with a special legal status. In principle, they could only be deployed to defend Tyrol, but in 1914 a legal loophole was found that allowed the Kaiserjager to be sent to Galicia. After the opening of the Italian front, however, they basically fought on this front section, in accordance with the original regulations.

Like the Feldjager battalions, the Imperial Guards had a horn on their hats and a small horn on their field caps. I will present the latter in this post. I can add a matching letter seal to it. [...]

Read more...

July 7, 2025The internet offers incredible opportunities even for old-fashioned guys like me who don’t really know how to use search engines optimally. I sometimes stumble upon exciting information based on the udder between the horns. The truth is that it’s not really possible to specifically search for something that we don’t know about.

There are quite a few mock badges that depict enemy soldiers in funny situations while the Monarchy’s bucks teach them the lesson. One such badge shows a fleeing Italian officer who, judging by his mustache, could be the Italian commander-in-chief, Cadorna. It’s a solid, nicely silver-plated badge. In terms of shape, material, and style, it’s similar to three other mock badges that I’ve shown here before. These badges are clearly the work of the same maker. Another series of mock badges in different look, material, and style was produced by the Arkanzas company, but these badges are typically “Arkanzas” and are otherwise also marked.

Until now, I knew nothing about the origin of the four badges that are different from the others, similar to each other, since they are not marked. Now, however, the internet has provided the solution. In one of the archives, I saw the badges on a page of a 1916 issue of the contemporary Hungarian satiric magazine, Borsszem Jankó. The intact text clearly identified the publisher as the designer (manufacturer). Even more interesting is that in addition to the four known types, there are also pictures of 5 other badges on the page. However, I have never had these as concrete, finished badges in my hands. They all depict enemies next to allied soldiers, in funny, uncomfortable poses. I do not know whether these were finally realized, or were they just drafts? [...]

Read more...

July 5, 2025The defense of the mountains south of the Pusster Valley was provided by the 49th Division. Its personnel varied a lot, but it was mainly composed of Tyrolean and Carinthian personnel. One of its most permanent units was the 96th Brigade. It consisted of several units, essentially mixed battalions, mostly Landsturm units from the area. I have already written about one episode of the defensive battle they fought here. In addition to the divisional badge, I have attached the badge of the 171st Landsturm to this entry.

The further mention of the division allows us to introduce another unit and another badge. This is the 165th Landsturm Battalion, which fought in the 96th Infantry Brigade in the Great War. I can attach a nicely stamped field correspondence card of the unit to the attached excellent badge. [...]

Read more...

July 3, 2025The Monarchy’s army was significantly reorganized at the beginning of 1918. Instead of the previous infantry regiments with four battalions, regiments consisting of three battalions were created. Previously, one battalion received mountain training and was assigned to the mountain brigades. Now these have ceased to exist. New regiments were organized from the previously separated battalions. With the replacements, in many cases, the surplus units from the regiments with more than the required four battalions were also directed to the new regiments. In this way, more than 30 new regiments were formed this year.

The 108th Infantry Regiment eventually received four battalions, because in addition to the two 8th and one 99th battalions originally intended for this unit, the previously separated I/81st Battalion was also added. The upper edge of the badge presented in the post shows the numbers of the three regiments next to the founding date of March 1918.

The new regiments were deployed on the Italian front, so their badges bear the images and names of that front. I have previously shown the badge of the 106th Infantry Regiment here, which has the inscription Piave and the image of the Venetian lion. The badge of the 108th depicts a mountainous landscape with the inscription Italien (Italy). The 108th Regiment was assigned to the 60th Division, which was stationed in the mountainous terrain between the Siebengemeinden Plateau and the Piave, on both sides of the Brenta river. During the June 1918 offensive, the division was part of the unit attacking Mt Grappa. The attack failed to break through the Italian third line. Having achieved minimal territorial gains, it essentially stalled on the first day. The division’s regiments were largely destroyed by artillery fire from the mountains.

With this in mind, the question arises as to when the badge was made? I think it was just before the offensive, perhaps with the purpose of improving the morale. The location of the photo attached to the post is unknown. The use of assault helmets suggests a date of 1918, as does the summer clothing. It depicts tired soldiers resting in mountainous terrain. It could have been made on Grappa. [...]

Read more...

June 30, 2025Badges were also made with the coats of arms of the Austrian provinces and the coats of arms of many cities. These are mostly beautiful enamel pieces and are publications of the war relief offices.

The Styrian badge is a particularly beautiful, large badge. It depicts the provincial coat of arms. Apparently, anyone could buy it, like all war relief products. It is relatively rare to see such a thing on soldiers’ caps, badges depicting the ruler were more widely used. Some units’ own badges, such as the 44th or 26th Infantry Regiments are worn by many. In these regiments’ group photos, half of the soldiers are wearing the regimental badge. [...]

Read more...

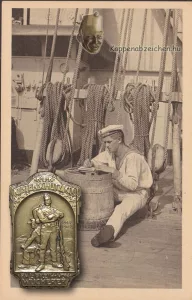

June 26, 2025The most successful unit of the Monarchy’s navy was the submarine fleet. The larger surface units were not deployed at all, with the exception of cruisers and destroyers. Submarines, however, were constantly deployed. They achieved important successes, especially in disrupting enemy merchant shipping. They also successfully attacked some larger surface units of the Entente navy, but these cases were more likely to be accidental, not targeted attacks.

I have already shown the submariners’ service badge in a wearing photo here. Now I am attaching a picture of a sailor who has this badge on his jacket again. The subject of this post, however, is a submarine propaganda badge.

The service badge is always present in the few wearing photos I know of, I have not yet seen the submarine Kappenabzeichen made in a wide variety in military photos. From this I assume that these served more propaganda purposes. There are some plate badges depicting battle scenes, like the one we are presenting now. And there were the beautiful, colorful fire enamel badges, with dozens of different decorations. I think not only the latter, but also the plate badges belong more to the patriotic badge category. [...]

Read more...

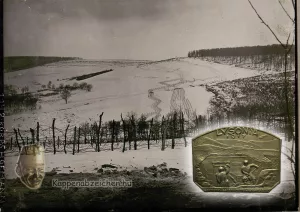

June 18, 2025The Italian front, which opened in 1915, had several front sections, each with a different character. In Tyrol, the fronts were mostly located between the peaks of high mountains, or in narrow passes between the peaks, which were mostly protected by fortresses. Further east, the mountains of Carinthia showed similar terrain. The Isonzo was the largest river near the border, with narrow valleys in its upper section, while the lower section had much larger and more extensive valleys. The estuary area was no longer mountainous, but rather hilly, more suitable for agricultural cultivation. Here, on the eastern bank of the river, lies the Karst plateau, the famous Doberdó battlefield.

The Karst is a hilly region, rising 100-120 meters above the river, and beyond the edge is flatter, with a highland character. Since there are no deep ravines or high peaks, it was easier for troops to move in this area. Moreover, one of the important Italian military objectives, Trieste and the Italian-populated areas of Istria, could be attacked in this direction. Therefore, the main direction of attack for most of the Italian campaigns was this area. Between May 1915 and August 1916, the front line stretched along the edge of the plateau. In the 6th Battle of the Isonzo, the Italians managed to push the front back by 20 km, to the central part of the plateau, to the front line of Fajti Hrib, Kostanjevica, Hermada.

The picture attached to the post depicts a detail of a trench on Fajti Hrib in 1917, vividly showing the improvised, shallow positions formed with great difficulty on the rocky plateau. The enemy could see into these from the heights in the background, so daytime movement in them was very dangerous. The attached badge is less detailed, we do not see trenches on it, only a landscape similar in nature to the photo. In the difficult conditions, both sides suffered huge losses [...]

Read more...

June 16, 2025The movement of troops and the provision of material supplies on all fronts of the Great War were basically carried out by railway. The expansion of capacity was continuous, and the reconstruction of tracks and equipment damaged by the enemy as the front moved was also a major task. Efforts were made to establish rail connections to places where there had been none before. The Prislop railway in the Eastern Carpathians was one such new railway line. Such was the case in several places with the railway line leading to the mountainous terrain of the Italian front, for example, the Julian Alps.

The lines close to the front were mostly narrow gauge. In several places they operated with electricity generated by small electric power plants. Such was the case, for example, with the line leading to Lake Bohinj. This reached the settlement of Ukanc. From there, a cable car system carried supplies to the high mountainous terrain of the Krn front.

The attached photo shows the wagons of a field railway. The badge chosen for the post, with its toy train-like train layout, fits in with these. [...]

Read more...

June 13, 2025The headquarters of the 6th Landwehr Uhlan Regiment was in the city of Wels, and it was founded here in 1885. The crew was mostly from the surroundings and from the Prague area. Therefore, soldiers with mixed Czech and German mother tongues served in the regiment. On the site of the regiment’s traditionalists, they emphasize the role of the 6th Uhlan in Limanowa battle, 1914. At that time, they provided the cavalry of the XIV Corps led by Lieutenant General Roth and successfully attacked the flank of the advancing Russian troops, threatening them with encirclement in the Neu-Sandez area. General Roth was later awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa for his achievements in the battle.

The regiment’s badge is a beautifully crafted fire enamel piece often seen in cavalry regiments. The oval disc contains the regiment’s letter and number, decorated with the Austrian imperial crown above. [...]

Read more...

June 12, 2025Boroevic Svetozar was one of the most respected Austro-Hungarian generals. His successes during the Great War are evidenced by his advancement in rank and position. I have already described his career in detail here. He rose from the command of a division to the command of a front, in the most difficult defensive positions. In the winter of 1914-15, he was a corps commander in the Carpathians, then on the Italian front he became the commander of the 5th (Isonzo) Army, and then the entire Italian front. The photo attached to the entry was taken of the colonel general during this period.

During the war, perhaps because of his Croatian origin, he was not really popular in the general staff. His excellent leadership performance did not elevate him to the narrowest circle. His performance was honored with the Knight’s Cross of the Military Maria Theresa Order, but he did not become a confidant of the monarch or the chief of staff. The services of the outstanding military leader of the Monarchy were not claimed by the Yugoslav successor state either. He died in Austria in 1920. [...]

Read more...

May 30, 2025There were three provincial rifle regiments in Tyrol. The third was located in the eastern part of the province. Its headquarters and one of its battalions were in the small town of Innichen, located at the end of the Pusster Valley. Innichen is an ancient city, there was a settlement here even before the Romans, and then one of the important Roman military roads led through it. Later, it did not become a prominent ecclesiastical or secular seat, so even during the Great War it had a population of only 2-3 thousand people.

The large barracks could have been built here due to the important strategic location of the place. During the Great War, the front was in the area of the mountain range on the southern side of the Pusster Valley. Unfortunately, I was unable to find out anything special about the building. After the Tyrolean riflemen, the Italian Alpini took possession of the block. It is still the barracks of the 6th Italian Mountain Rifle Regiment today. The building called Caserma Cantore is located at Georg Papiron Strasse 2. The Italian government wanted to modernize and expand it a few years ago. A training center with a permanent staff of 700 is planned to open here. The local population, most of whom are German-speaking, strongly opposes the development, fearing that the town will loose its ethnic character.

I have attached to the post the beautiful badge of the rifle regiment that once served here. [...]

Read more...

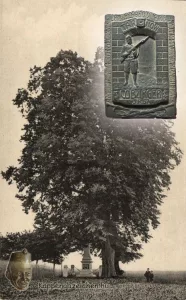

May 28, 2025Much has been said about the wooden statues made for fundraising, hammered with iron nails. I have also written here about the wooden shield of the Tyrolean 2nd Provincial Rifle Regiment, which is now kept by the Tyrolean Imperial Hunters Museum in Innsbruck.

I brought up the subject again because of a beautiful correspondence card. It shows a scene. The shield hammered with nails was taken to the front sometime in 1916. The card shows the moment of delivery. I do not know of any other similar case, it could not have been very common. Perhaps also because other regiments were deployed on fronts far from their headquarters, so delivery would have been much more difficult. [...]

Read more...

May 25, 2025The III. Corps was organized from the areas of Carinthia, Styria and the Shore province. The corps headquarters was in Graz. I have already written about the corps’ role in a previous post here. The Corps Headquarters building was located at Glacisstrasse 39-41 and was built between 1843-5 in the classicist style. The builder was Johann Christoph Kees, from whom the building also got its name: “Kees Palace”. According to Austrian sources, the building was used by the Austrian army in 1877. In 1883, the corps headquarters and the district Landwehr headquarters were also located in this building. The Austrian army rented the building from the owners until 1967, when the Austrian state purchased the property.

Originally designed as a customs house, the building was renovated in 2009 after decades of military use and is now used as a student dormitory. It has no particularly outstanding architectural value beyond the fact that it is the largest late classicist building in Graz.

The 3rd Corps had several badges, of which I have now uploaded the “Steel Corps” badge decorated with a laurel wreath. [...]

Read more...

May 20, 2025The 2nd Mountain Rifle Regiment (formerly the 27th Landwehr Infantry Regiment) was headquartered in Laibach (now Ljubljana). The regiment’s crew was of Slovenian nationality. A chamois can be seen on their badge. But why? On other regimental badges, animal representations more likely depict an eagle (often two-headed) or a lion. Why did a not very warlike herbivorous animal appear on the badge? For a long time, I had no clue that could explain this.

I recently planned a hike to Lake Bohinj. This region is already part of the Julian Alps, the terrain before the highest ranges. From there, you can continue to Triglav, which is the highest peak of the mountain range and of Slovenia. The front line ran along its southwestern side during the Great War. While browsing, I found photos of a chamois statue that resembles the animal depicted on the badge. The statue itself doesn’t look old, but since it’s also on the badge, there must have been an earlier version of it 120 years ago. The statue’s name is Zlatorog, meaning golden horn. Online sources are full of information about an old Slovenian legend, according to which the Golden Horn will lead the seeker to a treasure buried on Triglav. If only he meets the animal. Of course, no one has seen it so far, so the treasure is still up on the mountain. You can try!

The Golden Horn also got a statue in another settlement. But it doesn’t depict a chamois, but a mountain goat, with large, backward-curving horns. Unfortunately, the legend doesn’t say clearly whether Zlatorog is a chamois or a goat… [...]

Read more...

May 17, 2025A beautifully designed badge with (bored) bucks watching the sea on the Adriatic coast. This could also be phrased as soldiers heroically defending the coast. The coast defense consisted of infantry units and naval units. The thousand-kilometer-long Dalmatian coast was defended by only 6 battalions. The area around the ports was also defended by aging ships that were only used near the coast. The small force clearly indicates the low level of Italian (and Entente in general) interest. In addition to capturing a few smaller islands far from the coast, they only attacked the two major naval bases, with little success.

The coast defense units were subordinate to the command responsible for securing Bosnia-Herzegovina-Dalmatia (BHD Kommando). The defense was divided into three zones. The two northernmost of these were commanded by Major General Wucherer. The headquarters was in Mostar.

The postcard attached to the badge shows a bored sailor, also condemned to inactivity, writing a letter to those who remained at home. The coast guard and the navy also spent their time primarily patrolling, with little combat contact. The fleet had a few major offensive operations, but only submarines and naval aircraft were regularly deployed [...]

Read more...

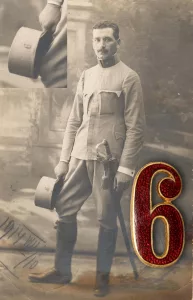

May 15, 2025A special badge and a special picture. The picture was shot on August 10, 1914 in Szabadka, at the time of mobilization, before marching to the front. Departure to the front, with stiffened cuffs, a neatly ironed uniform, a decorative sword, elegant gloves. And with the regimental number on the officer’s cap.

I have seen a few photos and I know many badges. I have never seen this pair, in any picture. I have never come across the enamel badge version of the regimental number. Maybe it was only made for the soldiers of HIR 6? It is also strange that it is already there in the first week of the Great War, that is, it was made in peacetime, and the guy obviously wore it.

However, if this was possible in the summer of 1914, then it had to be included in the otherwise very strict uniform regulations. It would be good if I had adequate knowledge about this, whether this number on the cap was actually in accordance with the regulations? If so, why can’t we find other numbers, neither badges, no photos?

According to experts, numbering the field cap was a requirement for the crew, and metal numbers were often used. The officer version shown here is therefore unique, since there was no need to put a number on the officer’s cap at all. The enameling could have been an improvement on a crew number. [...]

Read more...

April 28, 2025The reorganization of the cavalry divisions into infantry divisions affected not only the cavalry squadrons, but also the mounted artillery. The guns of mounted artillery was similar to that of traditional artillery units, only the personnel were riding horses for faster movement. After the reorganization, the horses used for fast movement were removed from the units. Also, the horse artillery units were given a new assignment. Thus, the artillery brigade of the 9th cavalry division was assigned to the 33rd division. And their name also changed: instead of the previous RtAR 9, after the reorganization they were given the name FAR 9K, where the letter K referred to the previous cavalry role (Kavallerie).

I wrote all this in detail because, in addition to the extremely beautiful badge, the presented correspondence card is also special. It was written home by the lieutenant of the aforementioned artillery regiment to his beloved on October 26, 1918, in the last week of the Great War. There is no sign that collapse was imminent. The letter writer dreamed that 3 months have passed since his last leave, and that he will have to wait another two months before he can go home again. Did he return safely to his beloved?

The 33rd Division was in reserve at the lower reaches of the Piave at that time, relatively far from the front lines. The main direction of the Italian attack was further north, and the inglorious situation when the armistice dates were misinterpreted and Italians took entire divisions prisoner did not occur on this front. So Lieutenant Szili had a good chance of getting home by the end of the year, the date written on the postcard. [...]

Read more...

April 24, 2025The headquarters of the 26th Landwehr and Landsturm regiments was Marburg (now Maribor, Slovenia). The Landsturm was the third tire of the army. The older age groups were drafted here at the beginning of the war. The regiments’ task was not to fight on the front lines, but to operate the areas behind the front in the military organization. However, by the autumn of 1914, most of the Landsturm and Népfölkelő regiments had already come under fire, because only these units could be urgently sent to the front line to replace the huge losses. The regiments suffered heavy losses. Most of them were disbanded in 1915, not replenished. A few regiments survived. These were later supplemented by younger age groups. Their combat value rose to a higher level.

This also happened with the 26th Landsturm regiment. As can be read in the margin of the attached correspondence, it was deployed in the most vulnerable sections of the Italian front. The regiment was used as separate battalions in the III. and IV. sections of the Italian front, i.e. in the Dolomites and Carinthia and in the upper reaches of the Isonzo in the 92nd and 93rd divisions.

The 26th Landsturm regiment did not have its own insignia, so I have attached to the post the enameled hat insignia used by the Landwehr regiments. It is possible that the Landsturm also used these insignia in addition to the Landwehr [...]

Read more...

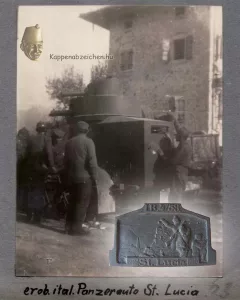

April 17, 2025The small town in Slovenia has already been featured here. Now it’s back because an exciting photo shows one of the town’s houses. The main subject, of course, is not the house, but the Italian armored car standing in front of it.

Let’s start thinking about the car. How did it get there? According to the inscription, it’s a vehicle captured nearby. The photo doesn’t show any damage, so it was probably abandoned due to a technical fault, which is how it ended up in Austrian hands. But this is also a very shaky explanation. The area around St Lucia is mountainous, sliced by the narrow valleys of the Isonzo and other rivers. The armored car was best used on roads, and the road network here was not very dense. But it’s also unclear how Italians managed to bring the car to the front line in the valley from the main Italian defense line on the opposite mountain plateau (Kolowrat)? But as the photo shows, it was somehow brought down and then abandoned in the valley.

The other important question is the location, of the picture. St Lucia is still a very small settlement with just a few streets (its current name is Most na Soci). In the background of the picture, the mountain Bucenica can be seen rising on the other side of the Isonzo. This hill and Mengore, as well as another hill further south, formed the Tolmein bridgehead, which played a prominent role in the 1917 breakthrough, the miracle of Caporetto. Near the presumed location, you can walk online using the well-known street view program, observe the surroundings and houses. I have tried to identify the building in the picture in today’s pictures. I am attaching the best result. The orientation and mass of the building are similar, the arrangement of the windows is not, but it could have been rebuilt several times in 110 years. [...]

Read more...

April 11, 2025The 57th was a Galician regiment, headquartered in the city of Tarnów. For Hungarians, Tarnów is primarily notable because it was the birthplace of Jozef Bem, the legendary commander of the 1848 War of Independence, or Grandpa Bem. The 57th Regiment was part of the 1st Division and saw action on all battlefields.

The letter seal attached to the post shows the monument erected on the Königgrätz battlefield, as does the opening picture. The regiment distinguished itself here in 1866, even though the Monarchy lost the war with the Prussians.

The regiment’s badge shows the town hall building in the background behind the gate, which stands on the city’s market square. The town hall, built in the 1300s, acquired its current form in the 1500s with a Renaissance-style reconstruction.

The predecessor of the settlement was founded 3 km from the present city centre in the 9th century. The city developed on its present location after the adoption of Christianity and the battles fought during the establishment of the Kingdom of Poland. Its first documented mention dates back to 1124. During the Polish Golden Age, it had 1200 inhabitants, and its water supply and sewage system were considered a very modern development. In addition to the Catholic cathedral, the city also had a community building of the Reformed Church and a synagogue, as well as a school. At that time, the city was the property of the Tarnowski family. The city was ravaged by Swedish troops in 1655, and later its importance declined with the cessation of Polish statehood. During the modernization of the Monarchy, the city began to flourish again with the construction of the railway. During the Great War, the Russians occupied it in November 1914, but after the breakthrough at Gorlice, it came under Austro-Hungarian control again. [...]

Read more...

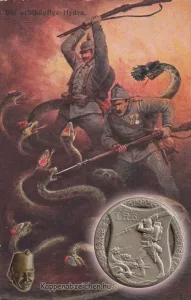

April 4, 2025The house regiment of Újvidék had a mixed national composition. Hungarians, Serbs, and Germans served in the regiment. This composition reflected the mixed ethnic groups of the Bácska and Banat, that were mostly settled in the 1700s a region that had been depopulated during the Ottoman era. The regiment was part of the 32nd Division and fought on the Russian front until February 1918, mainly assigned to the IV Corps. In 1918, the division was transferred to the Italian front.

The regiment’s well-known cap badge shows the 6er buck fighting a hydra (I think). I found a similar patriotic postcard, where this legendary animal has eight heads. Each wears the cap with the national colors of an enemy country. There is even a Japanese among the heads! Japan, of course, did not play a major role in the main European war theater. It plundered German property in the Far East. Its military supplies to the Entente were also significant [...]

Read more...

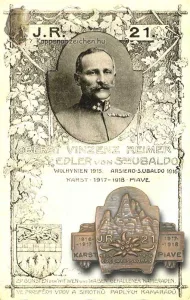

April 2, 2025A Czech regiment, headquartered in Kuttenberg. The beautiful badge of the 21st Infantry Regiment is a collector’s dream. It was probably made only for one series at the end of the war, in a small number of copies. Therefore, it is very rare. The main motif is the mountain, unfortunately unknown to me. It reminds me of the regiment’s stay in Tyrol. This regiment also belonged to the 10th Division, meaning that they were in this area from May to September 1916, more precisely in the III. Rayon, in the Dolomites. In the summer of 1916, they were assigned to the III. “Edelweiss” Corps for three months, which is also indicated by the badge. Obviously, belonging to the elite corps must have filled the crew with great pride, so it was immortalized on the badge.

The accompanying postcard shows a portrait of the regiment commander, Colonel Vinzenz Reimer, the Knight of San Ubaldo. Both the card and the badge listed the important stages of the war from 1914 to 1918. This is common to both. [...]

Read more...

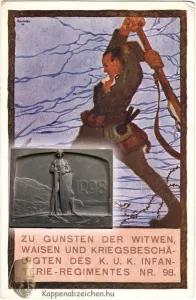

March 31, 2025Unfortunately, from now on, the esteemed reader will only rarely see a composition on this page where the cap badge and the accompanying illustration are closely related. The cards and wearing photos depicting Kappenabzeichen have run out. We have to be satisfied with field cards like the current one: a card issued by the regiment, but unfortunately the cap badge is not reflected in the motif. But this should not discourage us, as the beautiful badge of the 98th Infantry Regiment definitely deserves presentation.

This regiment came from the Czech-speaking part of Silesia (Hohenmauth), and a mixed German and Czech crew fought in it. It belonged to the 20th Infantry Brigade of the 10th Division. Until May 1916, it was on the Russian front, first in the 4th Army, and then in the Carpathians as part of the 3rd Army. They were again part of the 4th Army in the Gorlice breakthrough. They were transferred to the Southwestern Front for the Tyrolean offensive in 1916. In September 1916 they were sent to the Karst Plateau, and in 1918 they fought on the Piave Front. The background of the badge shows the seaward edge of the Karst Plateau, with the Hermada Heights in the background, where the regiment fought in 1917. [...]

Read more...

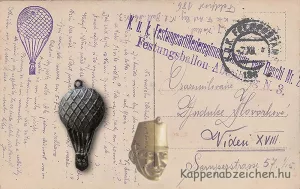

March 25, 2025The Monarchy had 6 fortress artillery regiments and a dozen of independent fortress artillery battalions. The six regiments were stationed in larger fortresses and fortress systems. Such were, for example, the fortresses protecting Przemysl or the port of Pola. The battalions were responsible for securing smaller fortifications and valley locks, primarily along the Italian border.

The 1st Fortress Artillery Battalion also had such a role in the eastern part of Tyrol, for example in the Dolomites. The location of the positional artillery strengthening the defense at the foot of the famous Drei Zinnen mountain group can be seen on contemporary maps. Part of the battalion was therefore not stationed in real fortresses, but in camouflaged firing positions established at strategic points of the defensive section. Their task was to repel attacks. Accordingly, they were not equipped with large-caliber, long-range guns, but with the usual field artillery equipment, the 8 cm field cannon, and the 10.5 cm field howitzers.

The beautiful badge of the 1st Battalion was already included here. Now I have taken it out again to present it together with the newly discovered field correspondence card. [...]

Read more...

March 22, 2025The emperor’s birthday was celebrated by the troops also during the war years. All contemporary reports and regimental histories mention this. It was a common custom. Franz Joseph’s birthday was August 8. So, based on the dating, the presented badge was made for the emperor’s 85th birthday in 1915.

I tried to find a suitable photo or card for the badge. The closest match is a birthday a year later (the last), which was held in Cetinje, the capital of occupied Montenegro, with the parade shown in the picture. I would say that such a badge could have been given to the honor guard, but I don’t know if a celebratory badge was made in 1916. I also don’t know how widely the badge was distributed? Since the occasion was celebrated by all the troops, I assume that it was a centrally ordered and distributed badge. This is somewhat contradicted by the fact that I have not seen any other one besides the piece in question, so it cannot be very common. [...]

Read more...

March 19, 2025The Kappenabzeichen of the assault troop of the 11th Cavalry Division is an exceptionally interesting composition. It is rich in detail, obviously modeled on a contemporary photo with extraordinary care. Moreover, it shows the assault soldier from an unusual angle, from behind, who, in addition to the usual assault equipment, also has a fokos (battle ax) on his belt. The postcard used as a background also shows a similar picture. The postcard was made for the regiment’s donation fund.

The cavalry divisions were used as infantry units at the end of the war, so assault units were also organized in the divisions. Usually, infantry divisions had battalion-sized assault troop. Former cavalry divisions, on the other hand, had assault half-regiments, which in theory meant a higher number of personnel. But it is also possible that these half-regiments corresponded in number to the infantry battalions, but since the fighting elements of the cavalry companies were smaller than the infantry companies, the number of soldiers in battalions and regiments in the cavalry was also smaller. Thus, the same number of assault soldiers came out for a higher organizational unit at the cavalry divisions. [...]

Read more...

March 16, 2025The regiment had Bosniak crew from the Sarajevo area, and it belonged to the 25th Division. This division consisted mainly of Austrian regiments, and the Bosniak regiment was complementing them. I have already written about the operation of the division here.

The regiment’s badge only shows the Bosniak coat of arms, not the name and number of the regiment. Despite this, based on several indirect sources, this badge can be linked to the regiment with a fairly high degree of certainty. I can present it because a correspondence card published by the regiment has finally been found. This is a commemorative card received for purchasing nails for the cladding of the “Iron Bosniak” statue erected to support widows and orphans of the regiment. [...]

Read more...

March 7, 2025To use a contemporary expression, we see a weapons insignia of aircrew on the postcard. I have never seen this or any other similar insignia depicted on a postcard. The insignia itself is not rare, the postcard is more so! [...]

Read more...

March 2, 2025The uploaded photo is interesting from two aspects. The artillery lieutenant is an aerial observer, as shown by the balloon badge symbolizing the air force on his collar lapel. Relatively few photos of the air crew have survived, and this is a particularly beautiful studio shot.

Another interesting thing is the Bosnia-Herzegovina-Dalmatia badge worn on his jacket. This badge was made for the force stationed in the military district bordering Serbia. It can be considered a front badge. We always think of the Balkan theater of war as secondary, despite the fact that the fierce resistance of the Serbs in 1914 contributed greatly to the thwarting of the Monarchy’s war plans. After the defeat of Serbia and Montenegro and the occupation of most of Albania, the Balkan front was completely relegated to the background. The British also had other things to do in Flanders and Mesopotamia, and the Monarchy’s military strength was also tied up by the Russian and Italian fronts. A weak corps-sized invasion force cannot be considered a serious military force in the circumstances of the Great War.

That is why it seems strange at first that an air force was also assigned to an invasion force of limited size and strength. It should be noted that the development of the air force took place at a rapid pace after 1914 and the Monarchy established many new flying squadrons. But even with these developments, they were unable to counterbalance the Entente’s air superiority on the Italian front. This superiority became overwhelming in 1917, but even then several flying squadrons were used on the Balkan front. There could have been many reasons for this, obviously the squadrons stationed in Albania were not intended for air combat but for reconnaissance.

There was one rather serious offensive operation of the Monarchy in this theater. Before the breakthrough of the Ottranto sea lock, the ports serving the Entente fleet were bombed, and there too, primarily the coal depots. The burning of coal reserves during the attack on the Italian and Albanian bases temporarily disrupted the refueling of ships. This significantly limited the maneuverability of the Entente fleet, which was very important for a successful attack. Marine planes from Cattaro and Durazzo also took part in this action. [...]

Read more...

February 25, 2025The inscriptions on the badges are often difficult to trace, because there are no direct sources. For example, the 81st Infantry Regiment has a badge with the inscription Lysonia on it. For a long time, while the Internet uploads were rare, I could not even tell what geographical unit this name refers to. A village? A region? A mountain? After diligent reading, I finally managed to find out that it is a 399-meter-high hill somewhere in the vicinity of Brzezany. The 32nd Feldjager had a job here in the fall of 1916. They had to help retake positions lost by other units.

It was known that this section of the front was defended by the German South Army, in which the Hofmann Corps also fought. There were mixed troops in this corps. Several newly formed Honvéd infantry regiments (308, 309, 310), Ukrainian legionnaires and the 35th Landwehr Regiment in the 55th Division, the 81st and 88th Infantry Regiments and the 32nd Feldjagers in the 54th Division. I first found a good map on Ukrainian pages that showed the area and location of the height. It shows that the Lysonia Heights is located south of Brzezany city on the east bank of the Zlota Lipa River.

Based on the recollections of the Ukrainian sources, the 309th Home Guards and the 32nd Feldjager, the picture then unfolded. After the great breakthrough of the Brusilov Offensive, the Russians tried to push back the front on this Galician front section as well, but they did not achieve a real breakthrough here. Between the breakthrough points in the north, Luck, and the south Olika, this section held its own well and successfully resisted the fierce Russian attacks. These were the largest in September and October 1916. According to Ukrainian sources, after September 2, the 35th Landwehr Regiment stationed on the hill suffered heavy losses and was replaced by Ukrainian soldiers. In the second half of September, they also suffered more than 30% bloody losses during the Russian attacks and were also withdrawn. The 32nd Jager were temporarily stationed here at the end of September. After that, the 309th Honvéd Infantry Regiment was sent here, which held the front line until mid-October, when the Russian attacks subsided. They were replaced by the 81st infantry.

The fighting was characterized by large mass attacks. The front lines changed hands frequently, and the captured positions had to be retaken by counterattack. The Hofmann Corps’ command praised the steadfastness of the troops in daily orders on several occasions. The defenses of the 54th and 55th divisions could not be broken through, but both divisions suffered heavy losses. In the center of the attack, on the Lysonia hill, the defending troops had to be changed every two weeks due to losses. The replaced units were rested and supplemented in nearby Brzezany.

Two types of badges with the inscription Lysonia were made. Since the badge shows a scene of position construction, I believe that the badge of the sappers and construction companies working here was made first. The existing sample was used to deliver the order of the 81st badge later. It is interesting that the badge is dated 1917. There were also fights here this year, but not with the same intensity as the year before. The map above shows the town of Brzezany, from where the Zlota Lipa River flows south. To the east is Lysonia Hill 399, with the Austro-Hungarian positions in green. On the other side of the hill are the Russian lines. [...]

Read more...